Following a trip to Edinburgh our roving architecture critic C. Gull delivers a characteristically grumpy assessment of some recent developments in the city.

Prince’s Street was oddly empty when we arrived in Edinburgh. The reason it transpired was that everyone was queuing to get into Pull & Bear, Stradivarius and Bershka in the St. James Quarter which despite its name is a big mall. We last saw these three stores together in Avenida Larios in Malaga, so one has no sense of being in Scotland, except the five photos of Scottish landscapes tacked to a little boarded up unit. If the photos had been taken in Yorkshire, we could have been in the Victoria Gate shopping centre in Leeds.

Prince’s Street was oddly empty when we arrived in Edinburgh. The reason it transpired was that everyone was queuing to get into Pull & Bear, Stradivarius and Bershka in the St. James Quarter which despite its name is a big mall. We last saw these three stores together in Avenida Larios in Malaga, so one has no sense of being in Scotland, except the five photos of Scottish landscapes tacked to a little boarded up unit. If the photos had been taken in Yorkshire, we could have been in the Victoria Gate shopping centre in Leeds.

This is not to criticise arcades per se. Avenida Larios is protected from the sun by an awning spread from end to end. Victoria Gate in Leeds is protected from the rain and wind by a glass roof, as indeed are Harvey Nichols and all the other shops in the many arcades that have been erected to encourage people to brave the grim Yorkshire weather over the last 200 years.

Of course, the folk of Scotland are made of sterner stuff. Up they come on the Waverly Steps, the coldest wind tunnel on planet Earth, onto the rain-lashed steppe of Princes Street, to wander past the closed department stores, Jenner’s, Forsyth’s, and House of Fraser and back along the other side, where there are no shops at all. The new shopping mall must come as a relief. At least it is warm and dry, and if you don’t arrive by car, it is free to enter. We arrived by car, paying £3.40 for an hours parking, heading to Boots to buy some anti-emetic tablets and escaping with 35 minutes to spare.

So, what to do with the rest of the time before we could check into our hotel? We could take a look at the Scottish Parliament – Was Enric Miralles having a joke at Scotland’s expense when he covered one side of the building with giant hair dryers to blow away the foetid hot air that MSP’s produce all day and the other side with giant canes for them to beat each other with?

Because parliament is closed we are forced to contemplate these important questions from the cafe of Dynamic Earth, the Michael Hopkins’ designed visitor attraction just across the road. This place, Dynamic Earth, seems the epitome of what modern architecture should be. It is a geological museum and as one approaches it on a long ramp, the history of Scotland is demonstrated in the form of giant standing stones from each of the periods of her geological evolution, from gneiss at the bottom to the gabbro at the top – nice! The building itself is a high-tech tent atop a castellated gothic base, which used to be the wall of a brewery when I was here as a student. It is set against the magnificent backdrop of Arthur’s Seat and just like Arthur’s Seat, it bursts forth like a volcano through the sediment of architectural history.

After checking in to our hotel on Queen Street, I wander up to George Street and contemplate the changes since Edinburgh was home. The Assembly Rooms, where we held our Rowing Club balls, is now a covid test centre and all the banks and finance houses are now clothes shops and bars. There are pavement restaurants everywhere and on a day like today the place looks quite continental. That is until you see the turd emoji, which brings us back to the St. James Quarter next to St Andrew Square. More generous souls than I might liken the tower of the St James’s Quarter to a cupcake: – it is still decorated with sprinkles of scaffolding – either it leaks or they are replacing the panels. As an icon of conspicuous, unnecessary and nauseating consumerism no appellation could be more apposite. So, there it is, spoiling the unique skyline of my favourite city for the next fifty years. Come back Bothwell and bring some gunpowder!

Never mind, there is always the Fruitmarket. Or is there? I have been promising my wife a visit to this little gem of an art gallery for years, but when we arrive there for brunch the following morning it seems subtly changed. The exterior looks the same, with Richard Murphy’s signature I-beams signalling the building’s mercantile past.

The Fruitmarket, as rejuvenated by Murphy, was not only respectful of the streetscape and the history of the building, but also of the artworks, providing a light-filled and calming ‘frame’ for the paintings and sculptures on display. That is still the case today and the café provides a convivial frame for an excellent brunch, but it is the new extension by Reiach & Hall, which strikes a jarring note. Not only is it so dark that a high viz vest would be appreciated, so that one could avoid bumping into other visitors (if there were any), but one feels the need for a hard hat to avoid the lowering steel I beams (a nod to Murphy perhaps?) which stick out pointlessly in all directions. And as for the artwork on display, a pair of steel-capped work boots would complete the ensemble for viewing the piles of builders’ rubble that have been left there as an ‘installation’

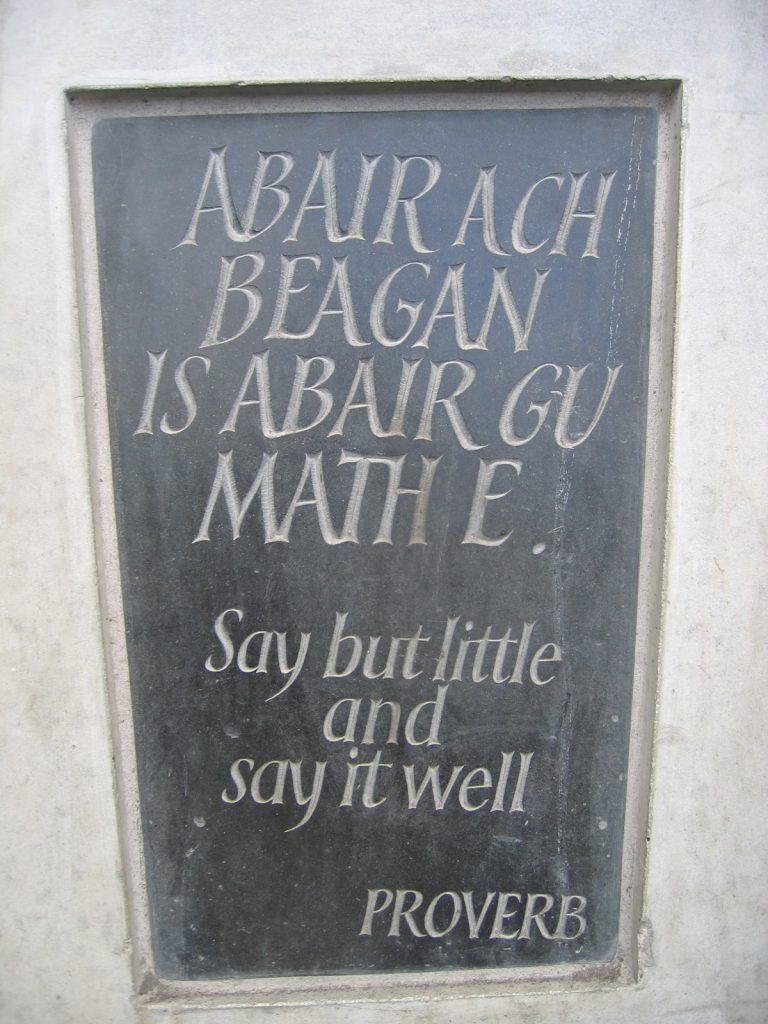

Whilst the argument as to whether the contents of the Fruitmarket Gallery Extension constitute art, or rather represent good art, is irrelevant here, there is little doubt in my mind that it represents bad architecture. The architects have jumped on the bandwagon of shabby chic, which will appear far from chic within ten years, and have confected a bombastic frame which will overwhelm any artwork placed within it, even if we could see it in the Stygian gloom of a space that has no provision for gallery lights. They have ‘said but little’ by simply ripping out the old walls and ceilings but they have not ‘said it well’.

They have joined Enric Miralles, with his weird Parliament building and Jesticho & Whiles with their giant cow pat of a hotel in the St James’ quarter to mess on the work of generations of fine architects. They will not be forgiven, and neither will the people who let it happen.

C.Gull