Our ongoing inability to create good places is, at least in part, a failing of urban design. Ombretta Romice, David Rudlin and Husam Al Waer argue that we need to redefine what we mean by urban design and recognise it as a distinct profession.

We have just been asked to review a book proposal: ‘What makes a good and sustainable city?’ was the gist of it. Another comprehensive list of principles, the same principles we have seen for… well, quite some time now, introduced by an alarmed overview of the big urban challenges we face. A very sensible proposal indeed. Yet, if only we had a pound for every time we have read such lists, we’d be rich, retired and living in an urban paradise. Or even better, our cities, towns and villages would be wonderful, healthy, just, for everyone. They are obviously not, nor are we rich (or retired for that matter).

We have just been asked to review a book proposal: ‘What makes a good and sustainable city?’ was the gist of it. Another comprehensive list of principles, the same principles we have seen for… well, quite some time now, introduced by an alarmed overview of the big urban challenges we face. A very sensible proposal indeed. Yet, if only we had a pound for every time we have read such lists, we’d be rich, retired and living in an urban paradise. Or even better, our cities, towns and villages would be wonderful, healthy, just, for everyone. They are obviously not, nor are we rich (or retired for that matter).

So, what is the problem? How is it that so much knowledge, and agreement, rarely becomes truly transformative? This is a question that we must address as urban designers, the failure to create good places is surely at least partly our fault. The fault lies not with our lack of talent, or vision, or powers of persuasion. The fault, in our view, lies in the way urban design has developed as a discipline. We have to use the word discipline because, of course, it isn’t a profession.

Urban design was conceived as the process of designing urban settlements as artifacts, via the mechanism of a masterplan

–

Back in 2019 the Academy of Urbanism together with the Urban Design Group invited representative from all the urban design schools in the UK to see if we could map out a territory for urban design as a precursor for an accreditation system for urban design courses and maybe even one day as the basis for a profession. Following that a group of us including, Kevin Thwaites, Mark Greaves and Sergio Porta continued the discussion over lockdown, the results of which are published this month as an open access paper in the journal Urban Design and Planning [1]. The aim of this (slightly shorter) piece is to summarise our arguments and conclusions, in the hope that we can start a debate, and perhaps even help create better places.

Our starting point was the notion that dates back to the emergence of urban design as a discipline. Urban design was conceived as the process of designing urban settlements as artifacts, via the mechanism of a masterplan, with scant regard to how we get from where we are now to the finished product.

Even when the discipline developed a more nuanced metaphor of an organism, there was still the notion of designing settlements and places to achieve desirable states (of ‘healthy adulthood’), to be kept and maintained, taking care of any ‘illness’ that may occur along the way.

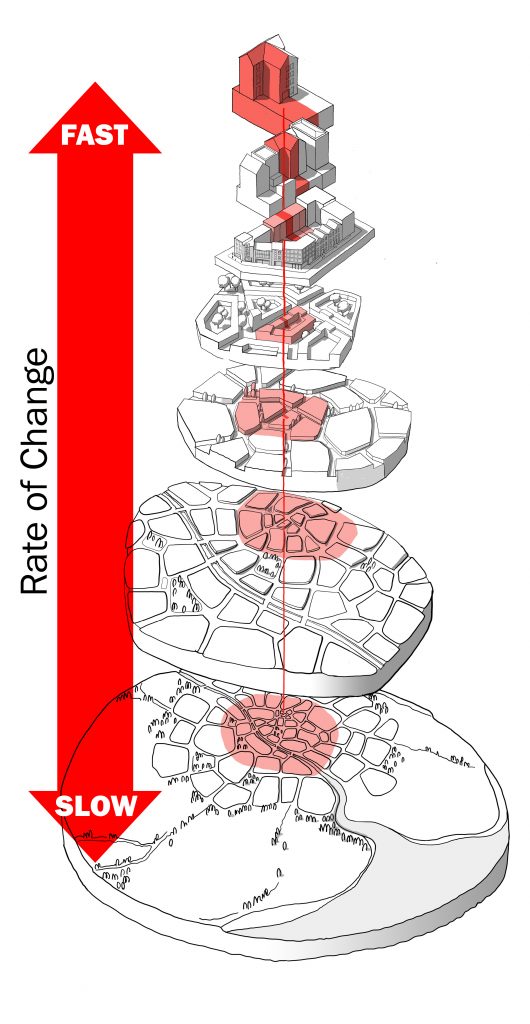

In both cases we lost the notion of time and the value of evolution, other than towards a fixed representation in space. Designing to achieve a desirable state, implies the need to maintain the output (a city, a neighbourhood, a space) in certain a condition. This, of course is a lost battle: time waits for no one and our environments, especially the built ones, are never static. The puzzle that makes them up has too many moving parts that are difficult to coordinate and control. We would accept that urban design has become better at managing complexity. But what it has failed to do is to recognise that complexity and change are, to borrow a phrase from computer programming, a feature, not a bug – they are what makes the system resilient (a word we will come back to in a moment) rather than a problem that needs to be overcome.

This is where our journey started, in seeking to define the discipline of urban design as a process of understanding, recording and shaping the built form of urban areas in a way that accounts for both complexity and time, without generating complete chaos. We use the words ‘built form’ because that is the medium that urban designers work in. It is perhaps because buildings are so solid and spaces so seemingly permanent that urban design has treated them as artifacts. However, we have known since Jane Jacobs and Christopher Alexander that they are nothing of the sort. Built environments are patterns created by dynamic complex systems and urban form is a type of organised complexity that we are able to influence and shape but not entirely control (or masterplan).

We may have understood this over the past 60 years, yet urban design as a discipline is yet to modify its original engrained conception of the city as a series of aspirational states to be pursued. This failure lies behind many of the problems that urban design faces when it works with other disciplines, and the hurdles we encounter in its education, practice and policy. it also explains, in our view, why urban design is not performing as it should in its present conditions.

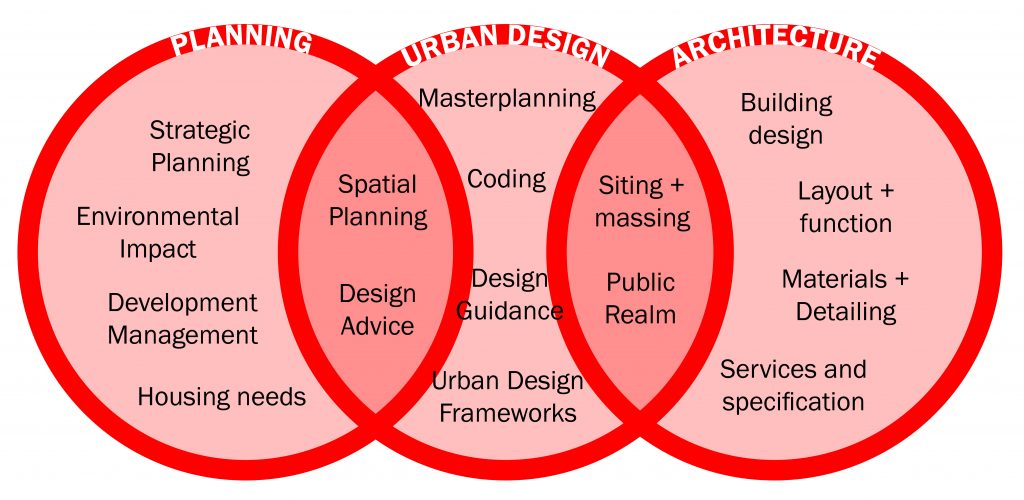

Discussions about the definition of urban design have focussed on scale. Architecture deals with buildings, landscape architecture with the design of spaces while planning deals with settlements and regions. Urban design has tried to squeeze inbetween but in reality the existing built environment professions work at a range of scales and the territory that urban designers seek to stake out as their own is therefore contested.

We have therefore sought to conceptualise urban design from a different perspective based on three points:

- The core of urban design is built form, in all its components, at all scales, and in all the way these come together to make up UD systems. Social, economic and environmental issues interact with these built forms with different degrees of friction. It is the task of urban designers to be aware of these interactions, and to respond to them through the manipulation of built and natural form (urban design is not urbanism, its content is more prescribed). By this we mean built form at all scales from individual plots to city regions – urban design is not confined to a particular scale.

- Resilience is the aim of urban design, and in particular how to achieve it through the manipulation of urban form. How do we account for time, complexity and therefore change with regard to urban form? The answer, our view, is the pursuit of resilience – the capacity of a complex system to adjust in time when circumstances require so that it continues to be successful. It is the resilience of the system that determines how it interacts with all other aspects of life, and how it evolves when life moves on.

- The knowledge base of urban design can be defined and agreed upon. It consists of the systematic collection of evidence of the urban forms systems that engage with all other life systems, to understand their successes and learn from mistakes. We need this to to know to practice good urban design. This knowledge must evolve as new evidence emerges; we are no longer in the realm of model theories, but of evolutionary theories.

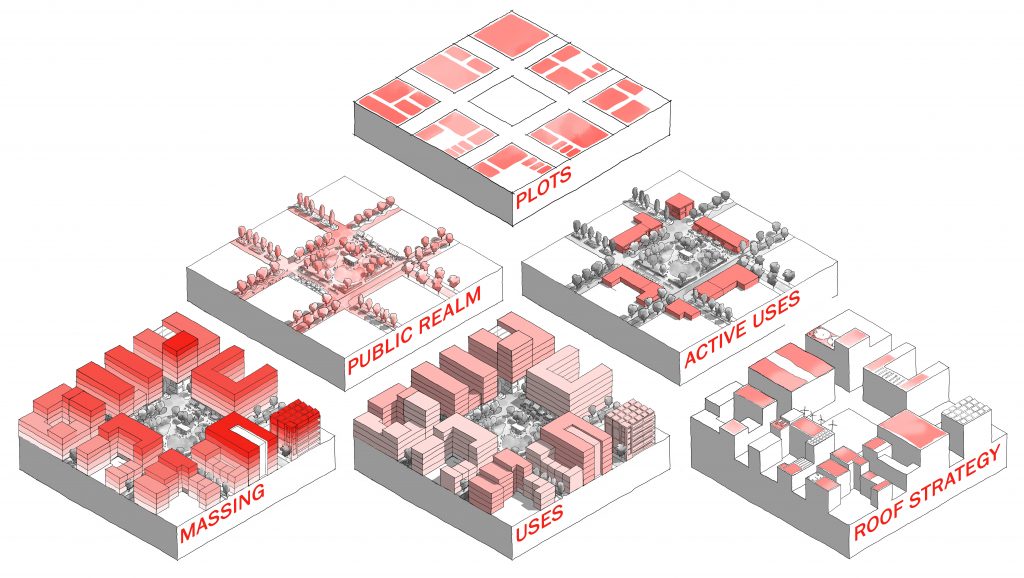

Let’s summarise these ideas briefly: urban design has one object of study and practice, urban form. Its goal is to produce resilient urban forms that support socio, economic, environmental needs at the time they are put in place and as these evolve. To do this urban designers need a base of evidence of how urban forms have afforded past and present performances. We should do so shaping spatial components (streets, plots, blocks..) and how these combine into different overall spatial systems.

As part of their knowledge base urban designers should possess a detailed understanding of:

- Urban Morphology and the historical development of cities’

- Urbanism including the economic, social and environmental factors that shape cities

An appreciation of:

- Development and the workings of the property market, the role of other professions, viability and property law

- Community and the process of consultation, participation and co-creation

- Regulation including the workings of planning systems, design coding and policy.

- Process , the time-based and uncertain nature of urban design and how it can be influenced over time

And fundamentally, the capacity to implement:

- The principles underlying adaptive places: The features of places that have been shown to lead to resilience including density, modularity, permeability, grain, legibility etc…

- The process of design: How urban form is shaped and organised across scales through masterplanning, spatial frameworks, regeneration strategies, place design, including design coding.

The question is two what extent interpretations of urban design today meet this definition. Certainly in education there are urban design courses that cover all of these points but very few that cover all of them. The same is true of practitioners. In private practice urban design tends to be the remit of people with an architectural training, with a focus on masterplanning By contrast, in the public sector, urban design is the remit of people with a planning background, with a focus on design policies and coding. Neither cover all of these points, in both cases there is a culture of exceptionalism in which examples of best practice are seen as the result of exceptional individuals achieving great things in spite of the system. We need to reconceptualise urban design so that good becomes the norm.

Which brings us back to the question of why urban design is not a profession? Without this there is no way of agreeing on a knowledge base, shared standards and objectives. Urban design remains whatever individual practitioners or course directors say it is. Yes, establishment comes with constraints, but also with the chance of demanding rigour and expecting quality.

How we get there is another question. Our proposal, is that first of all urban design education needs streamlined around a common core curriculum, aiming to teach how to shape urban form to achieve resilience, drawing from the seven areas of knowledge listed above. Secondly, the institutes that validate urban design courses, the RIBA and RTPI need to use these criterial in assessing courses. At present all urban design courses are validated on the strength of their parent disciplines; neither institute considers urban design separately. Thirdly, the built environment professional institutes including the RIBA and RTPI together with the Landscape Institute, the two highways institutes and even the RICS should incorporate an urban design accreditation as part of their professional memberships. Failing this the Urban Design Group should become the Urban Design Institute and urban design should become a profession in its own right.

We need to be much clearer what we mean by urban design – the world, our cities and places need it. We need to speak with a shared voice, assert our unique skills and claim our unique competencies. This will allow, in turn, all other cognate disciplines and their professions to be their best. All of the professions have trodden a similar path moving from loose agreement to a charter, remit and an agreed set of competencies and skills. If we can achieve this, then we will no longer need to keep publishing lists of what makes a sustainable city, place or neighbourhood.

[1] Romice O, Rudlin D, AlWaer H, Thwaites K, Greaves M, Porta S. Setting urban design as a specialised, evidence-led, coordinated education and profession. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Urban Design and Planning, https://doi.org/10.1680/jurdp.22.00023