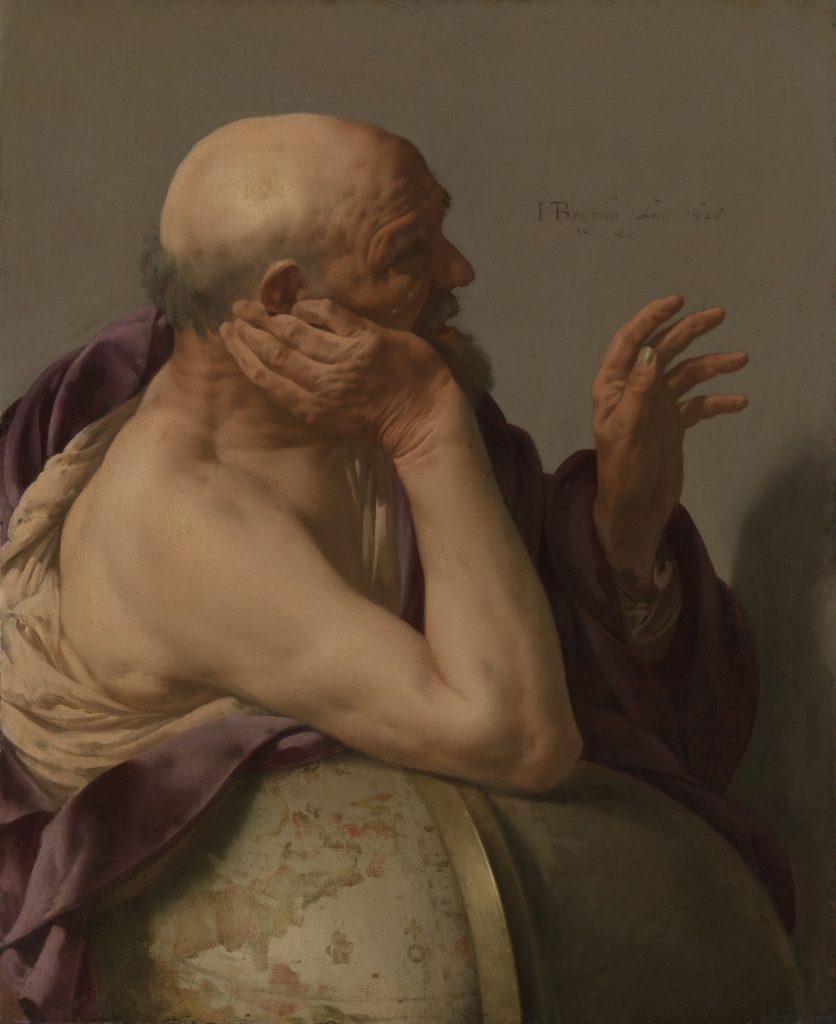

Everything Flows: What the philosopher Heraclitus can teach us about urban planning.

Andreas Markides reflects on change and 35 years of planning.

Many years ago, when I was still in school, I learned of a philosopher who lived in Ephesus on the coast of Asia Minor. This philosopher may be little known today, but he is still remembered for the following aphorism: “Everything flows”. As he explained, “no river is ever the same, as it is constantly flowing and constantly changing”, and he said that the same is true about so much else in life.

I have often reflected on this statement by Heraclitus and wondered about its significance and possible application to my own life. In particular, did it have any relevance to my own profession of traffic engineering and to the wider field of planning? At first I thought that it held no particular significance but, more and more, as I reflect on my 35 years in this profession, I realise that Heraclitus was spot-on.

For example, I have watched with much fascination (and no little amusement) how demand for different land uses changes over time. In the 1980s, a lot of us were building something which came to be known as a “business park”. No longer were we satisfied with industrial estates as those were ugly and outdated, because the Americans were teaching us that we needed to build business premises “in the park”.

We and the world around us change constantly until no more change can be afforded

Once we had satisfied our insatiable appetite for that particular import, we turned our attention and energies to another — the multiplex cinema. Subsequently, we moved to offices — each building boasting to be better, architecturally and locationally, than the one that came before it. I can still remember the fuss that was made about Ralph Erskine’s Ark, overlooking the Hammersmith Flyover, though it priced itself so highly that no tenant was found for some time. And so we arrive to the present day, which is all about housing and yet more housing.

Nothing exemplifies better our changing approach to land use planning than our policies on retail development. Remember the big push in the 1980s for supermarkets and then hypermarkets? These huge, monolithic structures were springing up everywhere, along with their associated sea of car parking. Then, suddenly, a voice — Mary Portas, perhaps — had the courage to point out that this trend was actually killing off our high streets.

There was tremendous opposition to questioning the out-of-town retail model and I recall how vociferously the main operators used every possible argument to stop any change on the grounds that they could only operate if they were allowed to have traditionally large stores, surrounded by car parking, on the edges of cities or towns. But change we did and, perhaps amazingly, we now have a Tesco Express and a Sainsbury’s Local on every high street and at most railway stations.

This change has now resulted in retailers such as Ikea reviewing its traditional way of operating, as evidenced by the Ikea “Planning Studio” on Tottenham Court Road, which opened in 2018. The Swedish flat-pack furniture retailer is also planning to open a store in the middle of Vienna, again with no parking spaces, although customers could carry smaller packs on public transport. As an added bonus, the new Vienna Ikea store will be a green building with public access to its roof terrace, offering stunning views of the city.

Shutterstock non-editorial license

In traffic engineering, we have also seen one of the biggest changes in approach and policy. Up until the late 1980s, traffic engineers would do everything possible to increase traffic capacities and keep traffic flowing smoothly. Then, a new gospel was proclaimed that “the more roads we build, the more traffic will be created”. This prompted a lot of soul-searching among traffic engineers. What were we supposed to do — provide traffic capacity or hinder it?

More recently, the concepts of sustainability and healthy living have gained ground, putting a last nail in the coffins of trip generation and road-building. Traffic engineers now know that, far more important than traffic capacity, is the provision of quality public spaces, more human streets, and places that contribute to creating healthier, happier communities.

Alongside the treatment of traffic, we have also been changing our approach to parking provision. I remember distinctly that in the late 1980s and well into the 1990s all my clients — whether these were developers, house builders or institutions such as hospitals or universities — would expect that I would make the strongest possible case for the provision of the maximum number of parking spaces.

That message started to become diluted with John Prescott’s sustainability agenda in the late 1990s with the result that nowadays a lot of our clients will ask that we make as little provision for parking as possible, to make more land available for either landscaping or more intensive development. It just so happens that reduced parking could also mean more sustainable developments but the fact remains that not only has our position changed, we have actually gone full circle from wanting the most to wanting the least.

Coming back to Heraclitus, it is indisputable that in my narrow field of traffic engineering as well as in the wider field of planning there is constant change; the river is indeed always flowing. However, if everything is constantly changing, does this mean that we are always wrong?

We were surely wrong in the 1960s when we were building what are now regarded to be awful and unsafe residential towers. We were also wrong subsequently when we started to build what we now consider to be soulless housing estates. Are we perhaps wrong even now when we are embarking (despite much questioning and cynicism) on a path towards a more sustainable world?

The answer is no. Heraclitus was correct up to a point. We and the world around us change constantly until no more change can be afforded. A volcano will continue to spew out lava and change in its form and intensity until it dies. A tree will grow until its trunk is eaten by a fungus and it falls to the ground. A river will continue to flow until it dries up. The volcano, the tree, and the river are gone, to be replaced by something else. Things cannot change in one set way indefinitely. The same is true with humans, but we alone are capable of controlling what happens next.

We are currently entering what can be described as our Sustainable Period (in planning as well as in every other activity). Everything up to now has been a stage in our evolution in both planning and traffic engineering and we are but a second away from the end-state. We simply must wholeheartedly embrace and adopt everything that sustainability entails. If we lose heart, it will probably mean the end of the world as we know it. Certainly, the signs are ominous, in terms of our natural environment as well as our own physical and mental health.

In conclusion, Heraclitus was mostly correct — everything changes, but only until we reach the end-state at which point we have no other option but to transform, or else cease. We must find and persevere along the path that protects our environment, provides for healthier living and creates quality places. If nothing else, even at this 11th hour and 2,500 years after Heraclitus’ proclamation, we will have proved him wrong.

Andreas Markides AoU is the principal of Markides Associates and former President of the Chartered Institution of Highways and Transportation.

Featured image from Shutterstock non-editorial license