Civic spaces are fundamental to urban life. Kathryn Firth asks how we can reintegrate the civic into suburban exurban spaces like malls and business parks.

“Difference” today seems to be about identity—we think of race, gender, or class. Aristotle meant something more by difference; he included also the experience of doing different things, of acting in divergent ways which do not nearly fit together. The mixture in a city of action as well as identity is the foundation of its distinctive politics. Aristotle’s hope was that when a person becomes accustomed to a diverse, complex milieu, he or she will cease reacting violently when challenged by something strange or contrary. Instead, this environment should create an outlook favorable to discussion of differing views or conflicting interests”. This is an extract of a 1998 Lecture by Richard Sennett at the architecture school in Michigan and makes the case for why diverse urban civic spaces or ‘the spaces of democracy’ as he called them are so important.

“Difference” today seems to be about identity—we think of race, gender, or class. Aristotle meant something more by difference; he included also the experience of doing different things, of acting in divergent ways which do not nearly fit together. The mixture in a city of action as well as identity is the foundation of its distinctive politics. Aristotle’s hope was that when a person becomes accustomed to a diverse, complex milieu, he or she will cease reacting violently when challenged by something strange or contrary. Instead, this environment should create an outlook favorable to discussion of differing views or conflicting interests”. This is an extract of a 1998 Lecture by Richard Sennett at the architecture school in Michigan and makes the case for why diverse urban civic spaces or ‘the spaces of democracy’ as he called them are so important.

Over the past decade this has been recognised in our town centres and urban neighbourhoods. The public sector is increasingly investing in the provision and improvement of civic space. Developers are also wise to this renewed interest in public space. A “public realm” provision is integral to the branding of new developments: these spaces are heavily programmed, hosting everything from yoga classes to farmers’ markets.

They fail to recognise that we are citizens first, and then employees

But what about sub-urban spaces? What about the large footprint offices, malls, campuses, technology parks, and enclaves of light industry that will continue to exist. The employees of these locations also increasingly expect “urban” amenities and their developers and managers are beginning to recognise the importance of the public realm and what it means to be a contemporary and appealing workplace. They understand that facilitating collaboration and knowledge exchange is key to attracting the best and the brightest and that their employees have rising expectations of access to amenities, the outdoors, and activities that contribute to well-being.

The likes of Google, Amazon and Facebook have suggested new paradigms for how to fulfil these objectives. Encouragingly, housing, supporting services such as grocery stores, and community infrastructure are being introduced to business parks. CBRE reports that suburban business parks are repositioning themselves to attract tenants and Savills have reported on the transformation that many business parks are undergoing to ensure they stay ‘on trend’, citing places like Green Park in Reading and Arlington Business Park in Theale.

However the design of these competitive corporate campuses inevitably focuses on amenities catering to the employee, indeed they are reminiscent of the old company town. Beyond retail and indoor fitness they provide little or no space for true civic interaction, nor do they connect to their host district or region. They fail to recognise that we are citizens first, and then employees.

Working recently in the US I became interested in how these suburban and exurban forms can truly embrace the civic at a time when business parks are being redeveloped and defunct malls repurposed or literally turned inside out in an era of online shopping. It seems to be a good time to also be asking these questions in the UK and to interrogate how we can reconfigure these suburban and exurban morphologies, make sustainability more than a buzzword and create inclusive places that are truly imbued with a sense of the civic – places and spaces that are not based around consumerism.

The Civic as Connective Tissue

To be truly public and civic these places must firstly provide not just for their workers and shoppers but contribute to their wider environment. Adjacent neighbourhoods must be able to “infiltrate” the territory of the life science, light industrial or healthcare campus, and indeed, the shopping mall. It is the generally underdeveloped interstitial zones between the campuses and the host suburb or town that provide the greatest opportunity.

The suburban civic realm should reflect why people moved to the suburbs in the first place – access to green space and proximity to nature and natural systems; a more intimate lifestyle, in contrast to the anonymity of the city. Hikers greet each other on a forest path despite not knowing anything about each other. But people seldom do this in an urban square or a shopping centre. We need to find opportunities to connect with natural systems, even if only remnants exist, and exploit their potential as a civic realm. We need to privilege green infrastructure over parking infrastructure.

We must find ways to extend the forest into the civic realm—literally and figuratively. The often daunting physical and perceptual distances between dispersed neighbourhoods and diverse communities can be bridged using natural systems, ecological systems that can also contribute to environmental health.

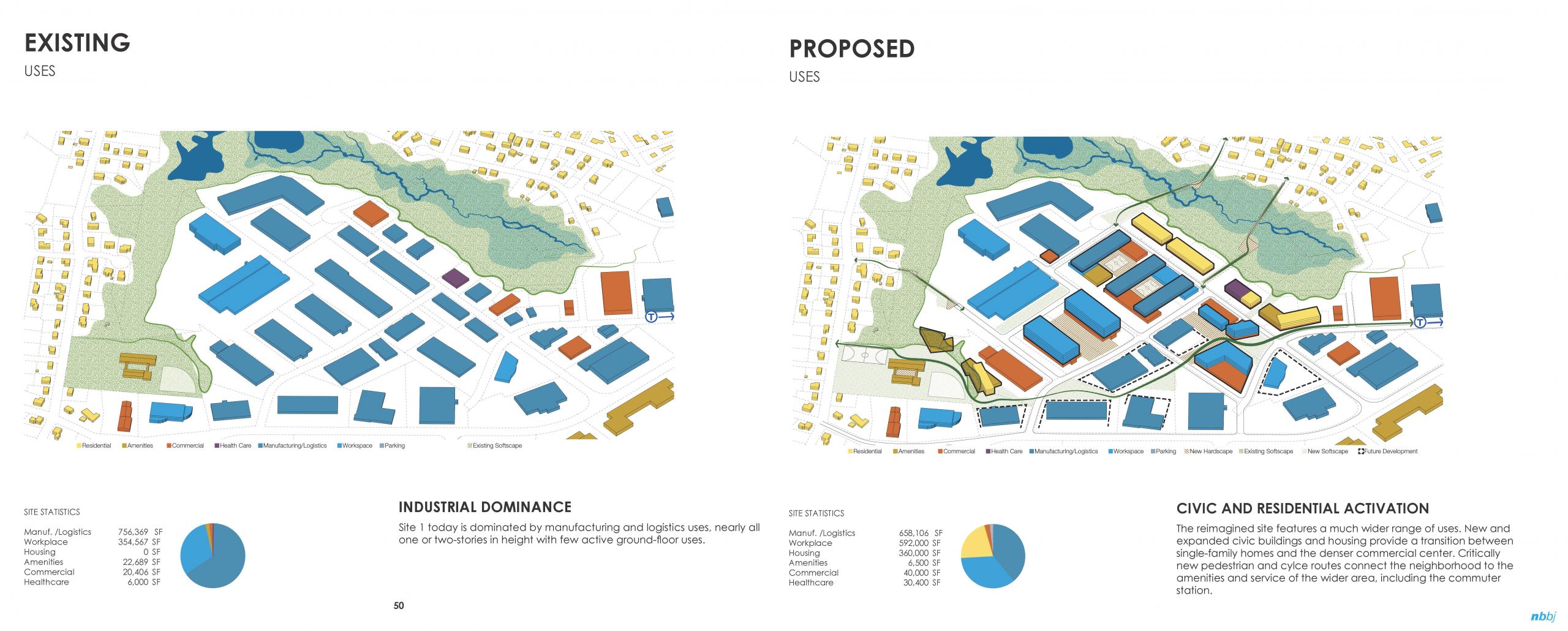

potential to retrofit a suburban light industrial area adjacent to a commuter station.

The new uses include affordable housing, community infrastructure new types of

workspace along with natural links to improve conectivity and wellbeing.

The built form should also maximize accessibility and frame a public realm that allows for inter-generational interaction, recreation, physical and intellectual mentoring, debate, and collaborative production. Indeed, we should seize the opportunity to explore new typologies and the throughout-the-week and around-the-clock use of space. The trade school integrated with seniors’ living both with access to shared outdoor ground and roof space, or the loading area that becomes a basketball court on Sundays.

We start to see precedents in the BeltLine currently being completed in Atlanta, the Promenade Plantée in Paris, or the Lee River Park, connecting the Olympic Park to the River Thames and the various industrial areas with residential neighbourhoods in between.

The civic is the acknowledgement of our responsibilities to our fellow citizens; it promotes social cohesion, and, one could argue, is more important than ever in this era of political discord. Perhaps the pandemic has helped us learn the importance of a civic realm where we know and look out for our neighbours; perhaps it will help mitigate the marginalization of the elderly, the infirm, and those simply viewed as “other.”

To incorporate these civic spaces into re-configured portions of the suburbs and exurbs, we will need to find ways to leverage space to accommodate them. To achieve those goals, we should consider mechanisms such as:

- development impact fees that require the private sector to provide spaces dedicated to civic activity;

- business Improvement Districts or Public Improvement Districts where adjacent landowners support yet give over some of their control of the space;

- locational criteria to ensure the allocated spaces can be active and safe;

- ensuring that these sorts of areas do not fall between the planning cracks, provide design guidance and codes that all new development and redevelopment must conform to before the market dictates its approach.

If we are to create a civic realm in the suburbs, we need to be proactive. While urban design alone cannot reinstate the civic, it can provide much-needed platforms and forums for the interaction and shared experiences that suburban residents and employees – no less than those in urban centres – want and deserve.

Kathryn Firth AoU is a partner at FPDesign