Frank McDonald AoU discusses controversial plans for a major bypass in Galway

Galway, Ireland’s western capital, holds the title of European City of Culture this year, largely on the strength of its vibrant arts scene and legendary party atmosphere. But it’s not really a ‘European’ city, in terms of transportation. If anything, it’s like a miniature version of Atlanta, the sprawl capital of North America, which is choked by its car-orientated growth. And Galway has done nothing else for decades apart from building roads, with big roundabouts named after the medieval city’s 14 merchant families (known as ‘tribes’).

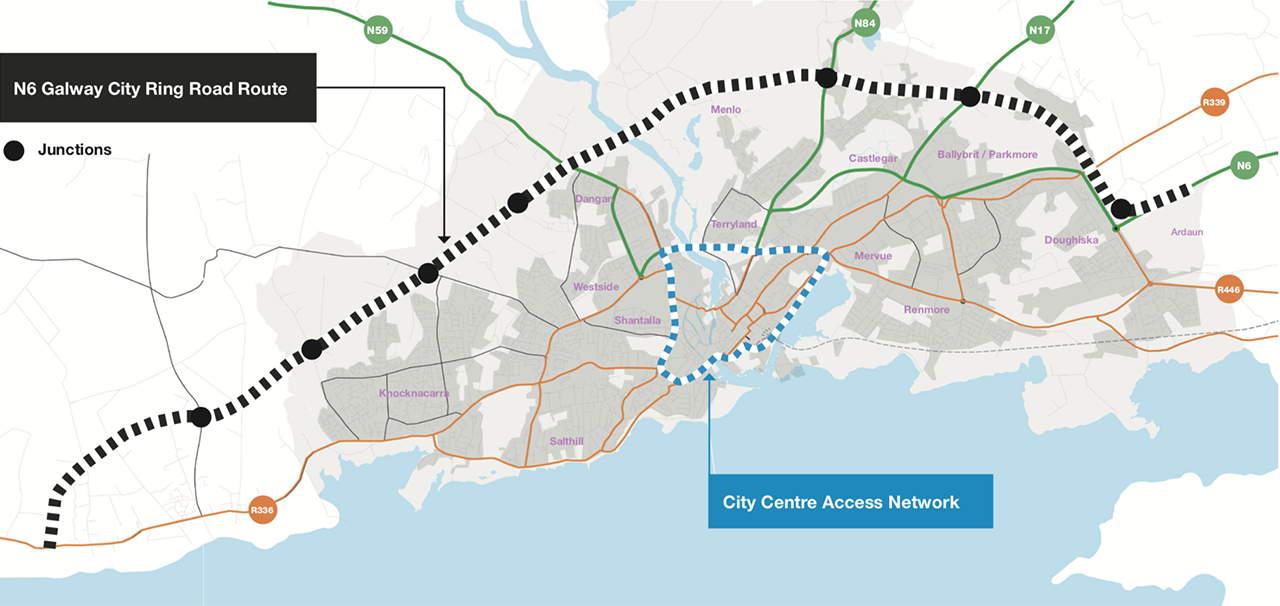

In truth, Galway is Ireland’s Carmageddon. And that dubious title would be massively reinforced if Ireland’s planning appeals board — An Bord Pleanála — approves the latest plan for a ‘bypass’, running from Barna in the west to Doughiska in the east. It’s not as if Galway (population: 80,000) doesn’t already have a ring road. It built one in the 1980s, but then the planners permitted all sorts of out-of-town ‘development’ along the route, with the result that it became traffic-choked too, and now apparently needs another ‘bypass’.

The local authorities – Galway City Council and Galway County Council, long slated for amalgamation — want to spend an estimated €650 million (£573 million) on this big new road, in the vain hope that it will ‘solve’ the city’s traffic problems. According to former mayor Niall McNelis, “it can take up to two hours to get across Galway city in heavy traffic” and the proposed N6 bypass would “allow us to take massive amounts of traffic out of the city” — a view shared by business interests in Galway, who are lobbying for it.

But the proposed 18km route would not actually function as a ‘bypass’, with only 3% of the projected 77,200 vehicles per day using it for that purpose, according to an analysis by Galway-based chartered engineer Peter Butler. The vast bulk of traffic would be ‘dipping’ into the city, its schools and inner suburban business parks along existing radial roads. As a result, it would function much like Dublin’s M50, which although conceived as a ‘national bypass’ of the capital, actually works as a distributor road for traffic seeking to access parts of the city.

Given its bias in favour of investing in roads, it’s no surprise that Galway’s modal split is heavily biased in favour of cars, accounting for two-thirds (66.7%) of peak-period trips in the ‘base year’ of 2012. Even after all of the measures recommended in Arup’s 2016 Galway Transport Strategy — starting with the proposed N6 bypass — are implemented, cars are projected to account for 67.3% of all trips in 2039, marginally more than they do at present. In plain terms, the strategy amounts to a transport cook’s recipe for condemning Galway to remain a motorised city.

The use of public transport is projected to increase from a miserable 3.9% in 2012 to just 5% in 2039. At the same time, the number of people walking to work is projected to fall from 26.3% to 24.9% over the same period while the number of cyclists is also projected to fall from a paltry 3.1% to 2.8% between 2012 and 2039. This contradicts the transport strategy’s central claim that it would give Galway “an opportunity to grow both physically and economically, offering better transport choices, and creating a public realm to be enjoyed by residents and visitors alike.”

Almost nothing has been done over the past 30 years to revolutionise public transport in Galway, or to improve facilities for walking and cycling. Take the Salmon Weir Bridge, where footpaths are barely more than a metre wide and congested with pedestrians on a daily basis. Typical of Galway, it’s to be given over exclusively to traffic while a new pedestrian bridge is to be built alongside, to get them out of the way. Meanwhile, the Clifden Railway viaduct piers are crying out to be topped by a bridge to cater for pedestrians and cyclists, linking NUIG with the city centre.

“Adding car lanes to deal with traffic congestion is like loosening your belt to cure obesity”

Lewis Mumford, 1955

But the Galway local authorities are so obsessed with catering for cars that they haven’t pursued this win-win idea. It is, of course, a form of myopia, induced by seeing the city almost entirely from the perspective of sitting behind the steering wheels of their cars, with guaranteed (free) parking spaces at their places of work. And in pursuing the N6 ‘bypass’, they conclusively demonstrate that they are locked into outdated 1970s thinking about transport planning — particularly the utterly discredited idea that you can ‘solve’ traffic congestion by throwing roads at it.

Way back in 1955, when I was five years old, the great American sociologist and urban planner, Lewis Mumford, warned that “adding car lanes to deal with traffic congestion is like loosening your belt to cure obesity”. Because the truth is that the more road space you provide in any city, the more it will fill up with traffic. Indeed, more than 30 years ago, in a paper called Jam Yesterday, Jam Today and Jam Tomorrow, the respected UCL transport researcher Martin Mogridge concluded that the only way to relieve congestion in an urban area is to improve public transport.

I have travelled all over the world, visiting more than 70 countries while reporting on UNFCCC climate change summits, adjudicating on The Academy of Urbanism’s European City of the Year award, or on holidays, particularly in Europe. As a result, I am keenly aware of international best practice in tackling traffic and transport to create more civilised urban environments. Bordeaux, Copenhagen, Delft, Freiburg, Stockholm, Vienna and Zurich, to cite just seven examples, have all worked to reduce the dominance of private cars, in favour of public transport, cycling and walking.

This step-change in how to deal with urban transport has been accepted almost everywhere in Europe because it’s a policy that works. It is now even true of once traffic-choked Paris, which I also know very well. Thanks to its mayor, Anne Hildago, and her predecessor, Bertrand Delanoë, central Paris is being transformed into a much more people-friendly place, with safe cycle routes, more space for pedestrians and, crucially, less traffic. Even a virtual motorway next to the River Seine has been turned into a pedestrian and cycle route, and a summer beach, Paris Plage.

Ireland’s National Transport Authority, which one might expect would be more enlightened as the regulatory body for public transport services, shares the Galway road engineers’ obsession with ‘road capacity’. It talks about how this would be ‘affected’ by “the subtraction of road space for cycle/bus lanes from the existing carriageways”, saying this “does reduce road capacity for those roads affected”. This, too, is outdated thinking that gives primacy to cars. The correct terminology for explicitly creating lanes for buses or cyclists on a public road is ‘re-allocating’ road space.

Still immersed in old thinking, the NTA says: “If it is socially desired not to reduce speeds for motor traffic (which is often the case for the motoring general public and through their elected representatives) then the road widths must be restored by some other means, such as road-widening, or the provision of relief roads, or alternative roads for motorists to use so as to avoid the lower capacity roads with cycle/bus lanes”. In other words, even the NTA regards cycling and road-based public transport (buses) as impediments to the ‘freedom of the road’ for motorists.

Under the national planning strategy, Project Ireland 2040, Galway (along with Cork, Limerick and Waterford) is targeted for a 50-60% increase in population over the next 20 years. The great danger is that much of this growth would happen on the outer fringes of the city, along the N6 ‘bypass’ corridor and on lands between it and the built-up area. If that were to happen, it would be in conflict with the over-arching aim of the strategy, which is that “at least half (50%) of all new homes” in the four second-tier cities must be located “within their existing built-up footprints”.

The proposed N6 ‘bypass’ also contradicts the Irish Government’s Climate Action Plan, not least because traffic using the route would generate 26,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide per annum in the opening year, rising to 35,000 tonnes per annum by 2039, as its promoters have conceded. Yet the action plan — published late last year — mentions roads only twice and motorways not at all, even though a major road investment programme, running into billions of euro, forms part of the current National Development Plan; the government simply hasn’t connected the dots.

Galway is at a critical point. Depending on the outcome of An Bord Pleanála’s deliberations, it can either travel down the route of having more traffic and more sprawl, or be pointed in a more sustainable direction, towards urban consolidation, compact growth and sustainable transport solutions. And while it is commonplace for the board to cite national policy as a reason for granting approval for infrastructural schemes, national policy can be wrong. And in N6 ‘bypass’ case, it clearly is. So I’ll end with this message to Galway: Don’t cling to a mistake because you spent a long time making it.

Frank McDonald AoU is The Academy of Urbanism’s writer-in-residence, an honorary member of the RIAI and an honorary fellow of the RIBA