Following the release of his book ‘Healthy Placemaking: Wellbeing through Urban Design’, Fred London AoU shares his framework for producing places with positive health outcomes

The places in which we live affect our health and wellbeing – for better or for worse. The need to rethink these environments to help us lead healthier lives began to be apparent towards the end of the 20th century, and the urgency to do so has been increasing ever since. Covid-19 has only made our predicament worse, with around 90% of deaths involving the virus among people with pre-existing health conditions1.

In recent decades, there has been growing awareness that the amount we consume and the ease of the lives we lead can create health problems attributable to lifestyles that result from the way our settlements are planned. Many ‘avoidable illnesses’ are associated with a lack of physical activity and poor diets, yet these can be ameliorated by health education, increased exercise in daily life, access to green space, reduced vehicular emissions and high quality urban and transport design.

To lead healthy lives we need environments that make it possible. A set of criteria has been narrowed down to seven ‘zero-tolerance health targets’: clean air; contact with nature; social interaction; feeling safe; living somewhere healthy; peace and tranquillity; and regular exercise. The outcomes are intentionally uncompromising, to highlight how far we are from achieving acceptable standards.

From theory to practice

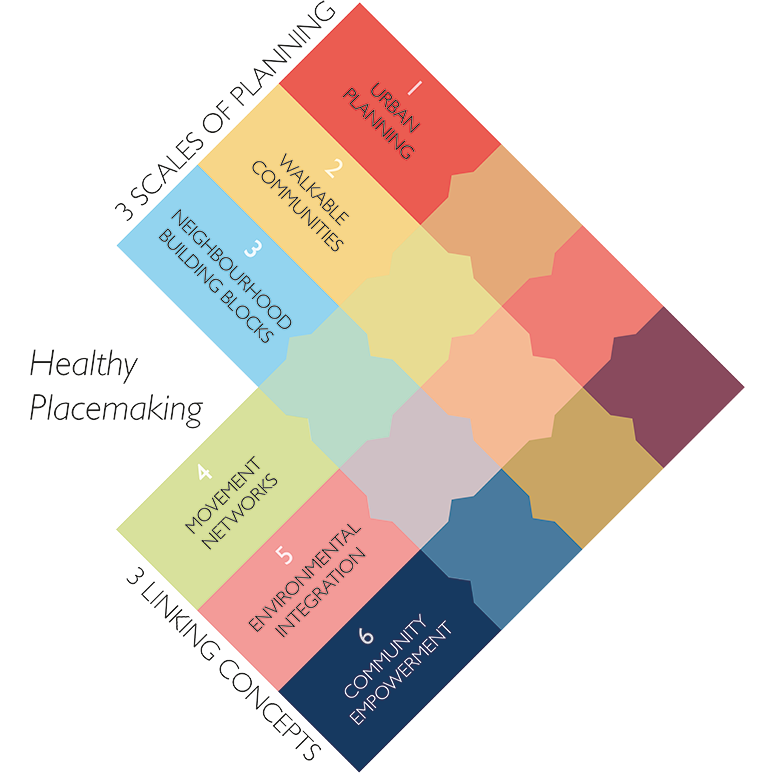

Six principles form the overall framework for my latest book Healthy Placemaking. They are as follows:

- Urban planning

- Walkable communities

- Neighbourhood building blocks

- Movement networks

- Environmental integration

- Community empowerment

These can be subdivided into two groups; three ‘scales of planning’ and three ‘linking concepts’. The interweaving of the grid produces different blocks of colour, for each of the nine intersections, to emphasise that the six principles all relate to one another, thereby characterising the ethos of healthy placemaking.

1. Urban planning

Equitable use of space: People living in lower-density neighbourhoods well away from the urban core expect to drive right to the centre where other citizens are living. The impacts on health include respiratory illnesses and dementia caused by poor air quality and the overuse of motor vehicles that discourages active travel and causes traffic congestion, curtailing the productivity of businesses. To address these challenges, thresholds must be introduced where changes of transport mode can rebalance mobility in urban centres, using easy and attractive forms of active travel.

In Vancouver, to prevent the urban sprawl that was creeping up the mountainsides overlooking the city, a densification programme was introduced for the city centre. This was based on high-rise apartment buildings whose residents could enjoy spectacular views of the still-uncluttered mountains; a clever, connected strategy that protected the natural environment and views onto it, while generating a vibrant and successful downtown benefitting from an excellent public transport system serving the substantial population.

2. Walkable communities

There are many advantages of living where we can walk to the places we need to access as part of daily life including local shops, health facilities, schools, workplaces, places to meet, eat and drink and green spaces for play and relaxation. The key components of a walkable community are a compact, mixed-use urban structure; daily needs within walking distance; and integrated green space.

Whether categorised as commuters, cyclists or pedestrians, people may shape-shift into any of these at different times. Recognising this can break down deep-seated definitions amongst the diverse users of the public realm.

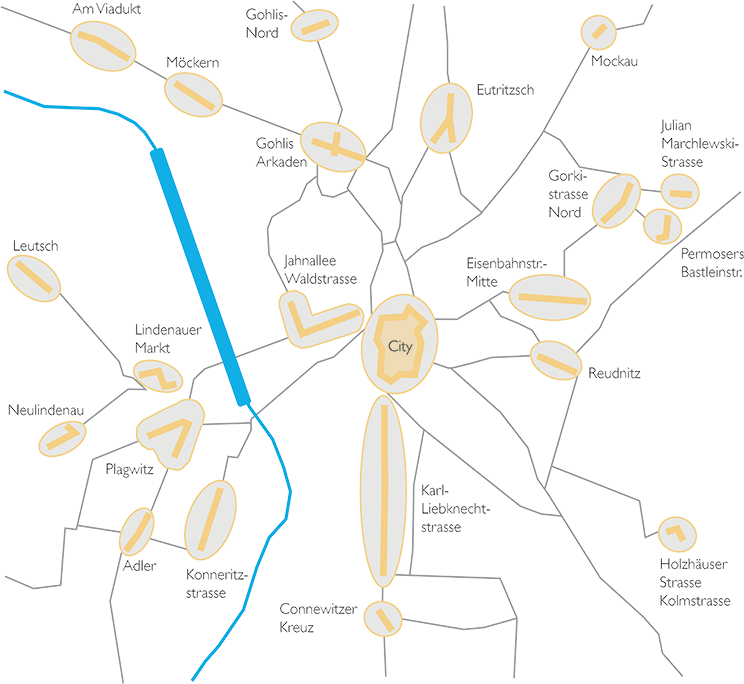

The urban core of Leipzig, winner of the Academy’s European City of the Year award in 2019, is the ‘living room’ for the whole city, working as a walkable heart. The strategy for the surrounding neighbourhoods shows local shopping streets 1-2 km apart that serve as focal points for walkable communities. The city centre showcases lovingly restored buildings, and in 2008 increased the car-free space in Leipzig’s ‘living room’ by 40%, creating a beautiful and healthy place for residents and visitors.

3. Neighbourhood building blocks

Reducing the level of planning to smaller-scale built form and intimate urban spaces enables well-designed neighbourhoods to have spatial frameworks that reduce social isolation, nurture community and offer maximum scope for the creation of therapeutic, human-scale environments. To encourage people to congregate, places need to feel safe, served by easily accessible social facilities and free from the impacts of traffic fumes and noise. Residential layouts work best when organised along well-overlooked public streets softened by trees and with cars parked discretely.

In Oakland, California, planners are inventive in finding ways to establish an identity independent from its more fashionable neighbour, San Francisco. Researchers from UCLA’s Latino Policy and Politics Initiative report that the ‘transit village’ of Fruitvale has been a boon to the surrounding neighbourhood without resulting in gentrification. Concerns that low-income residents would be forced to leave proved to be unfounded as researchers witnessed the village retaining existing residents and their Mexican-American culture.

4. Movement networks

The benefits of car use in urban centres are dwarfed by their downsides – air pollution, monopolisation of space (whether in motion or parked), speeding and road accidents, toxic particulate matter, obstruction of public transport, drivers regarding roads as the domain of cars and other road-users as secondary citizens, sedentary lifestyles and lack of exercise, fossil-fuel emissions and the impacts on climate change.

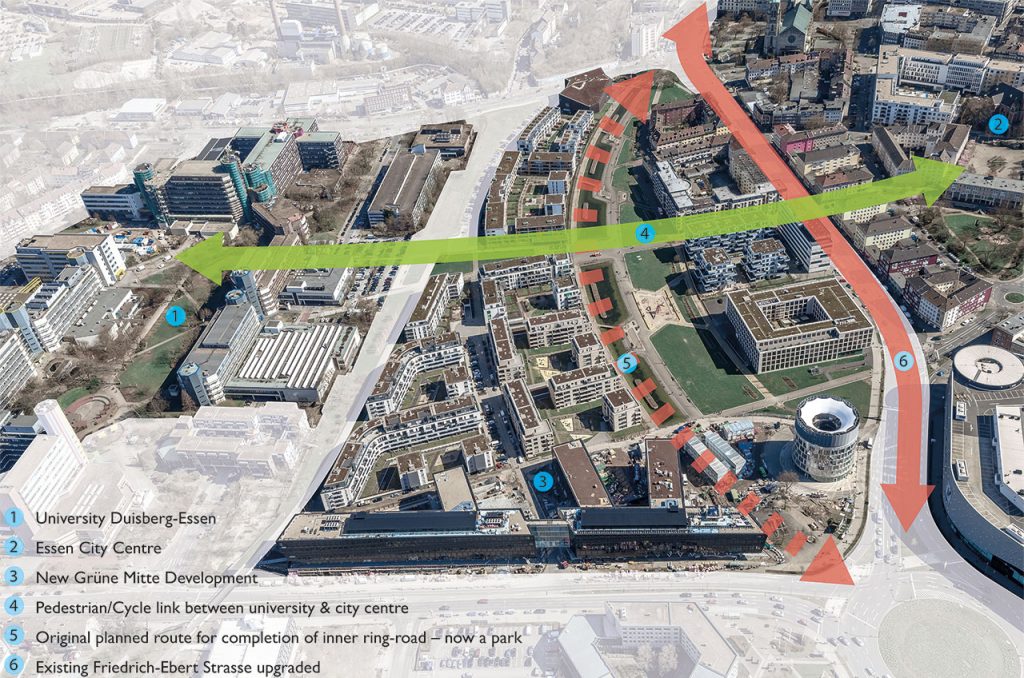

In 1999, at a JTP planning event for a brownfield site, the citizens of Essen, Germany, showed their preference for a public park at Berliner Platz in place of the planned completion of the city’s inner ring-road. And while it was not conceived as a health project, that is what it turned out to be.

Dotted red line: where the inner ring road was planned.

Solid red line: the existing road that was upgraded.

Green line: the pedestrian and cycle route connecting the University and city centre.

5. Environmental integration

Our positive response to greenery is triggered by areas in the brain, as demonstrated by neuroscientific research that combines reductions in stress with increases in wellbeing. Vienna, Zürich and Singapore are cities that have generated coherent strategies to establish a sustainable balance between green space and built form. By replacing low-density housing with taller blocks, housing numbers were increased while the quantum of green space was preserved.

Bishan Park, in Singapore, was created by the transformation of an existing, single-use concrete drainage channel into a much-loved public open space. The straightness of the outdated conduit accelerated the discharge of water into the sea. The new concept slows the flow by creating a meandering watercourse, stabilising the banks and reducing erosion to make a feature greatly appreciated by visitors and residents of the adjacent apartment blocks overlooking the park. The success of the project, which also addresses the need for clean water for domestic use, has increased demand for such initiatives in Singapore2.

6. Community empowerment

The involvement of communities is activated when people recognise the potential for the enhancement of their immediate environments. Such places can become a source of civic pride due to the quality of what has been achieved and the part played in the process by local people.

‘If you eat, you’re in’ was one of many catchphrases dreamed up by Mary Clear and Pam Warhurst, founders of Incredible Edible Todmorden in Calderdale, Yorkshire, back in 2008. Its heart remains there, but it has inspired hundreds of places worldwide where communities have adopted its empowering concept. Thus, when the construction of a doctors’ surgery came with a planting schedule of ornamental trees, Mary and Pam asked the doctors if they would prefer their patients to be able to pick fresh apples and pears from the outdoor seating areas. This pragmatic creativity is typical of the common sense that is the hallmark of their success.

Where next?

There are encouraging signs that the importance of healthy placemaking is gaining recognition at many levels, particularly among younger generations. The challenges we face speak for themselves and point to remedies within our grasp. This enables us to make progress towards the improvement of health and wellbeing, using as a template the framework offered by the principles of healthy placemaking. As the number of stones as yet unturned is immense, it is reassuring how much we can still do both to improve our health and protect our planet.

Fred London AoU is a consultant at JTP. His latest book ‘Healthy Placemaking: Wellbeing through Urban Design’ is published by RIBA Publishing and explores how we can plan to make our environments healthier.

1 Of the deaths involving COVID-19 that occurred in March 2020, there was at least one pre-existing condition in 91% of cases.

2 Design by Studio Dreiseitl, Überlingen, Germany

Featured image: Bishan Park watercourse designed by Studio Dreiseitl