The Academy of Urbanism Young Urbanists hosted an event on 15th September looking at the feminist city. Young Urbanist Kirsty Watt, organiser and chair, reflects on the findings of the discussion in relation to her research to date.

Content Warning: violence against women

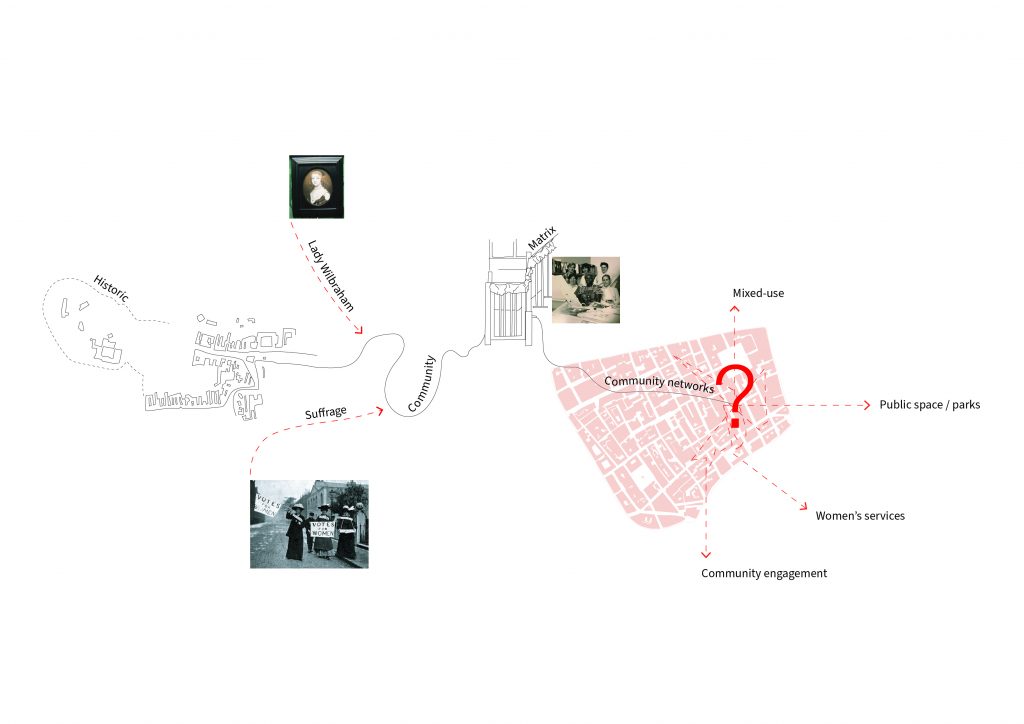

Lady Wilbraham – thought to have become the first female architect in the 17th century – supposedly had most of her work attributed to men. Now in the 21st century, we can be grateful that women are getting recognition within professional environments, but inevitably the question is raised of how we can use our female – and feminist – intuition to make the significant change that women like Lady Wilbraham would not have thought possible.

Lady Wilbraham – thought to have become the first female architect in the 17th century – supposedly had most of her work attributed to men. Now in the 21st century, we can be grateful that women are getting recognition within professional environments, but inevitably the question is raised of how we can use our female – and feminist – intuition to make the significant change that women like Lady Wilbraham would not have thought possible.

Having been through ‘Girl Power’ and ‘ladette culture’ we now stand on the other side still wondering how we can adapt cities designed by and for men to help – and importantly protect – not only ourselves but everyone else. As much as society is to blame for the ongoing violence against women and girls, we should ask as designers of the built environment in which this violence takes place, could we take some responsibility too?

Feminism is a core contributor to developing more sustainable cities and as the UN pushes countries to apply their SDG’s in an effort to ‘[protect] the very survival of our species’ we must consider feminist ideals as tools in striving for ‘reduced inequalities.‘ However, within the UK, even as the socio-political gender, race and class inequality gaps begin to gradually narrow, this is not being represented sufficiently enough within our built environment. Women make up over 50% of the UK population, and the ways in which they use the built environment – when different to men – are ignored. A feminist city – or a city designed with a gendered lens – works across silos to equally support all marginalised groups including, but not limited to, women, whilst simultaneously tackling issues of violence, perception of safety and spatial equality more generally.

Some would argue that feminist urbanism was initiated by the work of Matrix, a feminist collective in 1980s London, and at that point their practice was deemed revolutionary. Matrix worked to expose the gender-bias in architecture, and provide opportunities for under-represented groups to be heard, through innovative – and since almost abandoned – methods of engaging with the client, end users and wider community. One example shown in the recent How We Live Now exhibition at the Barbican Centre, was to include a space that the end users already understood – such as an existing meeting room – as a reference point within drawings and models. As a result, Matrix began to open up the discourse around the importance of women’s services, and the ways in which public funding and local councils can support women and girls, as well as making the design of spaces accessible to those not trained as architects.

The work of Manalo & White, and indeed that of the representative event speaker Aoibhin McGinley, continues the principles that Matrix explored with their latest project, the East End Women’s Museum. The East End Women’s Museum arose as a reaction to the Jack the Ripper Museum in London, originally proposed as ‘the only dedicated resource in the East End to women’s history’ (Khomami, 2015). The global interest in Jack the Ripper unfortunately speaks volumes about the lack of respect our society has for female victims. This is also prevalent in the killing of Sarah Everard this year, and subsequent warnings from the Metropolitan Police not to trust non-uniformed policemen, rather than reformation to a zero-tolerance justice system. Once again, women’s safety is considered to be a women’s issue rather than an issue for everyone. As urbanists, we should take this as an opportunity to better understand the impact the built environment has on violence and the perception of safety, and the role that communities can have in prioritising local issues and, ideally, in the design of better cities for everyone.

Deborah Broomfield, a PhD student and one of the panel, described the feminist city as a feeling rather than anything that can be prescribed in it’s physicality. Having spent the last year trying to uncover what interventions could be proposed within existing cities to make them more feminist, I was confronted with the fact that she was absolutely right – feminist urbanism isn’t so much a look or a style, it’s more a way of thinking. It was interesting to hear the opinions of the ladies on the panel, and the way that they spoke of the power of community. David Sim within the acclaimed ‘Soft City’ speaks of the positive impact of densification implemented ‘at a pace where local businesses and residents can be part of the journey.’ Although this is a reference primarily to incremental urbanism, it also lends itself to community involvement as a tool for architects and urban designers within the process of adapting existing historic cities.

Something I have become aware of during my time researching this subject is that as urbanists we are unlikely to have all the answers or know the needs of individual communities but rather we need to be asking the right questions to the right people, and importantly meeting those people where they’re at. In 2017, the Scottish Government concluded that “experience suggests that engagement rarely changes planning outcomes,” (Scottish Government, 2017) quite probably as a result of community participation just being a tick-box exercise rather than something that drives the design and planning process. Consequently, austerity in community participation is a common issue which must be rectified if we are to strive for an intersectional feminist built environment. When considering the ‘inter-cultural city’ and the idea of inclusivity and fairness, Charles Landry notes that there is often an emphasis on the inclusion of ‘sought-after high potentials’ only, being those able to work, perhaps already being trained professionally, in itself posing issues of accessibility and gendered roles. However, cities such as Madrid are beginning to research and quantify diversity and inclusion, with an inter-cultural observatory. In The Making, a group of architecture students in Glasgow who spoke of their latest community project Make Big Noise, brought the below quote to my attention and posed the question, if a forest is an exemplar diverse environment, should a feminist city be a collection of forests?

“Our farms need to be forests, our gardens need to be forests, our schools need to be forests”

Vandaya Shiva

In summary, a feminist city relies on policy and built design that supports and incorporates not only women, but all members of the local community. The end result may vary depending on a variety of factors, but the communal vision remains the same. It should therefore be noted that a feminist city in no way stifles the creativity of the architect or urban designer, as evident from the work of feminist collectives such as Matrix, but provides processes that will aid in making the project more successful, sustainable, and useful to the community in a way that some architecture currently fails. Architecture, art and urban design are known to reflect the socio-political opinions of the period, and we no longer want to be creating a built environment that shows a relaxed attitude towards assault and harassment. Urbanists must be leading the movement to safer spaces, with those most at risk their highest concern.