Author: Andreas Markides

During the Academy’s recent Congress in Cambridge I met new and old friends and saw exemplar developments with sustainable living as their key objective. I was fortunate to visit north-east Cambridge which TOWN and U+I are developing as joint master developers into a mixed-use development of more than 5,000 residential units. The project is led by Swedish firm KS Architects and, whilst inspiring, it made me consider the key ingredients of a good place – however defined!

We all know what makes a good place – or rather, we all recognise a good place when we see one. It’s those sun-drenched Italian squares, full of bustle, small pools of people conversing loudly and groups of children (let’s call them street urchins) playing football amongst it all. It’s also those north European neighbourhoods neat and orderly with lots of beautiful landscaping (and the odd orchard thrown in the mix) and cyclists dominating the streetscape. It’s the chaotic scenes that confront a western visitor at an Asian market, loud, colourful and a little shambolic for our own western taste.

We all rejoice in such places and many of us want to copy. We write whole essays trying to teach each other about what appears to be an elusive art of Placemaking. The concept originated in the 1960s when writers such as Jane Jacobs offered ground-breaking ideas about designing cities that catered to people, not just cars and shopping centres. Others soon followed, including Jan Gehl who proclaimed ”First life, then spaces, then buildings -the other way round never works” -not forgetting Aristotle of course who, several thousand years ago, had stated that ”A city should be built to give its inhabitants security and happiness”.

And now we have a multitude of noble approaches -Anne Hidalgo’s (or should it be Professor Carlos Moreno’s) 15 minute city, Barcelona’s Superblocks, Melbourne’s 20minute neighbourhoods and (many years ago now) the Dutch Woonerf, a social-architectural concept which considered new ways of living. Even Tirana’s Kid Friendly Urban policy represents the spearhead of a grand plan to refashion Albania’s capital city as a more sustainable and better place. All these different methods striving for the same thing -to move away from a standard engineering formulae and closer to what one might call the ‘’human’’ angle. Consequently, we have the Liveability Index in Melbourne, TfL’s Healthy Streets Index, the Walk Score in America and so on.

The big question is: why do we still fail to build better places? Why, despite so many people’s noble efforts, do we continue to create lifeless residential neighbourhoods and unattractive squares? Why is a good place still the exception to the rule -the odd one out that merits a special visit by professionals, rather than the everyday standard enjoyed by everyone? Why was it necessary for the Academy to visit another development at Marmalade Lane in Cambridge which has become an exemplar, instead of the norm, for sustainable 21st century living?

Or put in another way – how can we achieve better places, better communities and better living? What ingredients are essential to successful Placemaking? In my discussions with many people and in reading different books I have come across words which are familiar to and often quoted – such as Vision, Long-term Strategy, Quality, Public Engagement, Stewardship, the Environment and so on.

These are all very important. Below I identify five which are my personal favourites.

Leadership must be at the top of any list. It provides direction and inspiration, requires courage, and someone to lift their head above the parapet and do what is right. A leader must not waiver; their conviction will bring all others along. There are several such examples, but it will suffice for me to mention the regeneration of London’s Docklands under the command of the ‘’Tarzan of English politics’’ Michael Heseltine.

Time to successfully implement a project is of paramount importance because nothing can be achieved overnight. It therefore requires patience and a long-term strategy with different pieces falling in place on the way. Often a long-term strategy is sacrificed for the sake of short-term opportunistic policies but reassuringly we still have many examples where different cities have avoided the temptation of short-termism in order to deliver something exceptional. Wulf Daseking was the city planning officer (Oberbaudirektor) in Freiburg for nearly three decades and the outcome is admired throughout the world; remember that Sir Peter Hall had labelled Freiburg as the ‘’new Jerusalem’’.

An integrated approach is also required. What does this mean? It means architects, planners, engineers and economists working together rather than separately. A significant obstacle to that is the existing compartmentalisation of professions. It is high time that all Built Environment disciplines came out of their silos and worked collegiately as a team of BUILDERS. This will spark various (and surprising) ideas and will undoubtedly deliver a project which will have been considered from any number of different perspectives. It is probably as a result of this more integrated approach that several northern European countries are now giving greater prominence to nature in the places that they build. Their landscape architects (and their sociologists) are having a greater say in the design process.

Partnerships between stakeholders will provide focus and momentum to any project. Partnerships should be created at different levels -from grassroots (engaging meaningfully with the people that will be using and living in that space) all the way up the hierarchy to different government departments, institutions, funders and developers. A notable example of this has been Eindhoven’s Triple Helix partnership which consisted of the mayor’s office, the local university and private sector.

Cars are the elephant in the room. The nominal report Traffic in Towns has long warned we need to ‘’tame this beast that we all love’’ for otherwise it would come to dominate our lives – and it has. Everything that we build is predicated on the requirements of the car. Thankfully this dependency is now questioned and after a period of carrots (more cycle lanes and better bus provision) English councils are wielding the stick – congestion charging, Clean Air Zones (in Birmingham, Bath, Bristol and many more) Ultra Low Emission Zones (ULEZ) in London or more recently Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs). There are countless more schemes around the world attempting to curb the influence of the car. Notable amongst these is Pontevedra in Andalucia the mayor boldly banned cars from most of the city in 1999. The city has since been reaping the rewards in reduced car accidents, reduced air pollution plus an influx of some 15,000 residents into the city.

So, have I succeeded in outlining a recipe for successful Placemaking? Somehow, I do not think so! My recipe breaks down when one considers London’s Borough Market and thousands of other similar places. Borough Market is in most respects a very successful place as it is often thronging with (happy and loud) people; it is vibrant and very popular. And yet it did not come about through any particular leadership or as a result of a long-term strategy nor is it in any way a green project or one that is endowed with good quality materials. It is just a place under a few railway arches, next to a busy highway. Nobody planned it in any sense that we know; it grew organically almost of its own accord.

Does London’s Borough Market mean that we (the designers of places) have no role to play? If good places simply happen, why don’t we just give up? The answer is that, notwithstanding Borough Market (and several other similar places) there are countless more places that prove the opposite. An obvious such example is the regeneration of Kings Cross/St Pancras which by the late 20th century had become a symbol of blight and decay with derelict buildings, railway sidings and contaminated land. How was the subsequent successful regeneration achieved? In addition to the Vision for the site (encapsulated in the document Principles for a Human City) success came as a result of a strong partnership between the developer Argent and the landowners who were London and Continental Railways and DHL. This point also identifies the huge significance of Land Ownership and its assembly: Every masterplan starts with many good intentions but inevitably all of them will be confronted with the Herculean task of multiple land ownerships. This leads not only to delays but crucially to the complete dismantling of the idea of a unified project; hence the breaking up of what space is available.

The conclusion is that can facilitate the creation of good Placemaking -just like we can (if we allow greed to predominate) create monstrous jungles as evidenced by what has been created in Vauxhall over the last 20 years.

What really makes a successful place is the people. It is the people who make a place (in the same way that a place shapes people). For a place to flourish it needs people who care about their community, who have moral values (what are these?), who believe in themselves, who have aspirations, who…….

All these attributes are beyond the control of a placemaker but nevertheless they constitute the most essential element to what we are, almost in vain, trying to build. This reminds me of Epicurus, the philosopher who is wrongly remembered for advocating pleasure when in fact he had been asking a more fundamental question ‘’how would people achieve happiness’’? He concluded that one essential ingredient for that is friendships i.e. the community that we create and function within.

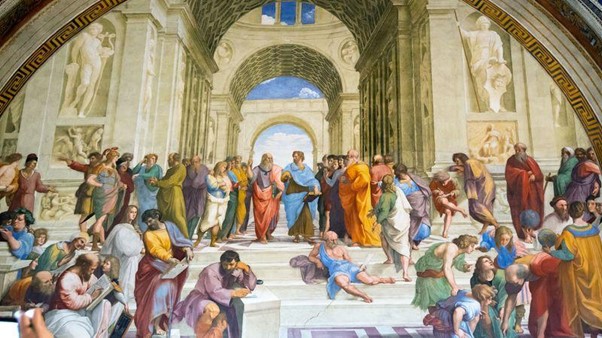

Does this mean that our profession is redundant? Are we, the professionals, ever going to achieve the elusive chimera of a “good place”? The answer of course is NO -we will deliver good places but so long as we do it with people in mind. This means we should design places with the people and for the people. There can be no better representation of that (certainly in my own eyes) than the agora in ancient Athens where the space and the people gave rise to something that continues to enrich our lives to this day. When we say people we mean active citizens as encapsulated in the famous quote by Pericles: “we do not say that a man who shows no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business. We say that he has no business in our polis, at all”.

This quote makes it clear that good Placemaking is not quite enough; it also requires appropriate contributions from the people that use that place. It’s the blend of the two that goes on to create human civilisation. (See above Raphael’s fresco in the Vatican of ‘’The School of Athens’’.)

Note: polis in Greek means city – and the use of the word politics by Pericles does NOT mean politics as we know it today. It means a citizen who is active in the affairs of his/her polis