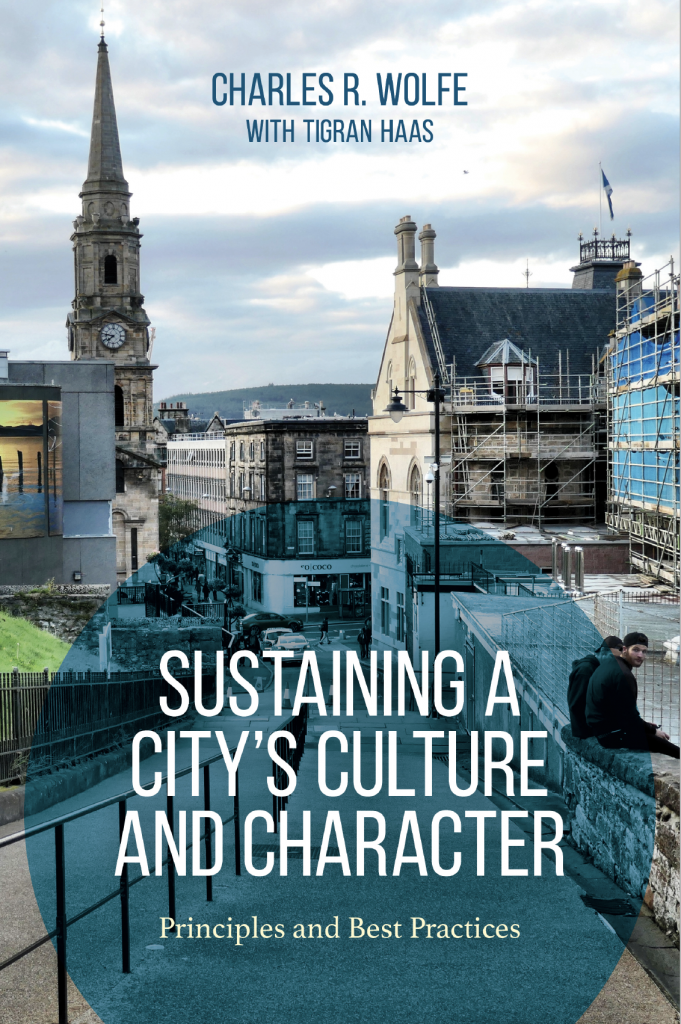

I bet a lot of us have complained to our neighbours about our local area losing its ‘character’ or signed petitions against new developments we consider to be ‘inauthentic’; As Chuck Wolfe asks in his new book Sustaining a City’s Culture and Character, what do these terms mean and why do we care about them so much?

Urban redevelopment often stirs deep passions and provokes bitter debate. This looks set to continue in a post-Covid world, where changes in work/life balance have caused us to radically reconsider how the cities and towns should grow and change. But let’s take a deep breath, pause, and in that quiet, really listen to what our cities are telling us. As we emerge from pandemic times, we need to consider with care what it means for a city or town to acknowledge and honour its traditional identity and essence, as it transitions to something new.

Urban redevelopment often stirs deep passions and provokes bitter debate. This looks set to continue in a post-Covid world, where changes in work/life balance have caused us to radically reconsider how the cities and towns should grow and change. But let’s take a deep breath, pause, and in that quiet, really listen to what our cities are telling us. As we emerge from pandemic times, we need to consider with care what it means for a city or town to acknowledge and honour its traditional identity and essence, as it transitions to something new.

If you could redesign the town or city you live in right now, what would it look like? How would the traffic circulate, what type of new housing would you like to see and where, what kind of green spaces would you have, how would you make sure it accommodates the pressing needs of climate change and social justice? And how would you even begin to redesign it all, when towns and cities are such complex places, full of history and cultural significance yet also beacons for the future? Urban communities fuse everyday life with notable events and places and mix common custom with the custom-made. Cities are blends rather than absolutes. Authenticity, culture, character, and uniqueness are just words with meanings that depend on who is using them and in what circumstances. They depend on context, so discussing them requires reference to the basic concepts of change and survival.

Let’s listen to what cities are already trying to tell us about themselves,

Although we can summarise some generic marks of urban culture and character—waterfronts, say; or the appearance of cities from well-known urban bridges— such generalisations are pretty unhelpful unless we take the time to learn and reflect some more. The stories behind the Brighton and Margate beaches, the Tyne Bridge in Newcastle, or the Pulteney Bridge in Bath all vary based on time, place, use, and more. Memories formed by gazing from the Pont Neuf in Paris contrast with those from the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. Local—as well as personal—circumstances still matter in a digital age.

Three years ago, in my London flat, I discussed expatriate life with Plamen, a Bulgarian-born handyman, as he finished a small painting job. We compared living experiences in multiple countries, and Plamen may have said it best in a poetry of the day to day: “Everywhere, there is home, work, and food,” he said. “Each place, they mostly have the same things, but what changes is which one of these is better.”

Fast forward to July 2021. In Newbury, I saw a blend of changing times, near-post-pandemic. A big-screen television and food cart graced the closed entry of a former Debenhams, with AstroTurf and lounge chairs there for the taking and a small crowd was watching the tennis from Wimbledon. Albeit transitional, this may be perfectly legitimate ‘authenticity’ and ‘character’ for these changing times.

In the United Kingdom, Changing Chelmsford has contributed a decade of diverse, community-led initiatives; more recently, a Colchester project has championed the return of the high street in a new form, with explicit avoidance of a top-down model. The community-led South Lanes Project has instead moved forward under the rubric of ‘community, creativity and commerce,’ with the additional ‘C’ of ‘collaboration’ involving a broad range of stakeholders.

In another example from my new book, I spend time explaining how an old Covent Garden fruit and veg stall evolved into five bricks and mortar outlets and ended-up in a retrofitted rail arch near Waterloo. Today’s stall is an online-based delivery service, with a new generation of the same family that started the business, with the same customer service ethic that guided the founder. Again, this strikes me as ‘authenticity’ and ‘character’ evolving.

We cannot predict how even a well-planned city will evolve, but we can assess a city’s unique attributes and imagine how and why they may change or combine. Successful cities are the ones whose policy makers, urban designers, historic preservation professionals, and elected officials try to understand urban change in the context of their cities’ particular blend of characteristics and circumstances.

We need to understand urban change—and cities’ unique characters—based on a commitment to critical, on-the-ground observation, the assessment of local culture, the importance of integration with the world stage, and the dangers of an indiscriminate application of consultant-driven, overly generic, or discipline-specific approaches. Let’s listen to what cities are already trying to tell us about themselves, to allow them to have a future that really works for residents now, and for those to come.

Adapted from Sustaining a City’s Culture and Character by Charles Wolfe, published in hardback with Tigran Haas on 24 June by Rowman and Littlefield, as the final book in a trilogy designed to raise awareness of the intrinsic identity of urban places and the importance of avoiding urban renewal that is out-of-scale, context, or character.