As climate conditions will only grow more severe, our response needs to be greater than anything previously imagined, says Karl Limbert AoU

Looking back over the last five years it’s difficult not to view the arc of history as bending progressively towards climate justice. Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, there has been an incredible momentum to tackle the great sustainability issues of our time.

In the last year alone, the UK Parliament has declared a climate and biodiversity emergency; the UK Government has legislated to reduce all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050; and two-thirds of UK local authorities have now declared local climate emergencies.

In the private sector, traditionally carbon-intensive industries, like automotive manufacturing, are being radically disrupted by new low carbon brands like Tesla; more than 900 architectural practices have now declared a climate and biodiversity emergency, pledging to use their skills to accelerate the implementation of mitigation and adaptation measures across the UK built environment; and a low carbon social housing scheme won the 2019 Stirling Prize. Progress at last! Right?

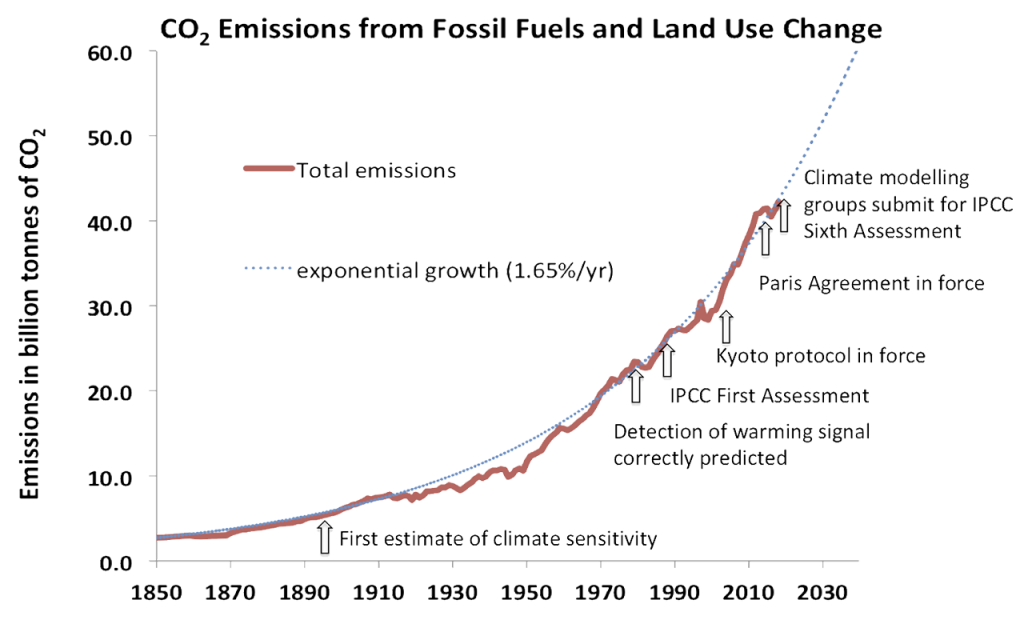

Well, kind of. But more honestly… not nearly enough progress. In the period between the Kyoto Protocol in 1992, and the EU net zero target being set in 2020, global greenhouse gas emissions continued to rise exponentially. True, the UK achieved some impressive emissions reductions during that period, but they were mostly from the power sector, and in particular from the phase-out of coal-fired power generation. Emissions from the built environment remained frustratingly static, and for every prize-winning / pathfinding / low carbon demonstrator project, there have been literally hundreds of other developments churning out high carbon factor buildings like there was no tomorrow. Our ability to talk about this stuff isn’t really in question. Our ability to do something about it, at a truly meaningful scale, most certainly is.

So, what would it take to really scale up our response to the climate and biodiversity emergency? Firstly, we need to properly understand the magnitude of the issue. The global response to the Covid-19 pandemic provides a useful calibration here. One of the unintended consequences of the lockdown implemented by states around the world has been a sharp drop in greenhouse gas emissions.

On current estimates, it seems that the world is currently on course for an emissions reduction of approximately 8% by the end of 2020. Coincidentally, this is roughly equivalent to the emissions reductions we will need to see every year for the next decade to limit global warming to less than 1.5°C, and to achieve the ambitions of the Paris Agreement. The implications of this are clear: achieving net zero will require nothing less than a radical transformation of everything we do. Climate emergency declarations and pilot projects alone won’t get us anywhere near close.

It follows from this that we urgently need to upscale our ambition. The philosopher Timothy Morton talks about global warming as a ‘hyperobject’ – a problem of such vast spatial and temporal dimensions that it seems to elude conventional thinking. We need to be undertaking ‘hyperobject scale’ mitigation and adaptation projects throughout the 2020s if we’re going to have any chance of properly responding to this emergency.

What would these projects look like? We are beginning to see the first few emerge – Bristol City Council’s ambitious ‘City Leap’ investment programme for place-wide decarbonisation by 2030; ENGIE’s transformation of the former coal fired power station at Rugeley in Staffordshire, into a mixed-use, low carbon development for 2,300 new homes; ENGIE’s redevelopment of the former dye works at Manox, Greater Manchester, into a new 400 home low carbon community; and the Welsh Government’s bold proposals for a nationwide low carbon housing retrofit programme.

Thirdly, we need to help the governments improve the rules of the game. The UK’s 2050 net zero target needs to be supported by a comprehensive framework of policy and legislation to guide delivery. As urbanists we have the skills to positively influence this. One area that needs immediate attention is the interface (or lack thereof) between energy systems planning and town and country planning. The RTPI recently noted that the capacity of our planning system to help deliver the low carbon heating, cooling and power needed to get our communities to net zero is almost completely lacking. We need to facilitate an interdisciplinary dialogue between planners, urbanists and energy specialists so that we can create new models of net zero placemaking.

Fourthly, and following on from this, we need to introduce new actors into the placemaking value chain. The findings of this year’s Place Alliance Housing Design Audit show that traditional models of development aren’t delivering the quality we need. The placemaking sector needs its own Tesla. A disrupter that can invest in and deliver transformation at scale. It’s not yet clear where this disruptor will emerge from. Perhaps the public sector in the form of a publicly owned net zero development company? Or maybe from the energy, infrastructure or tech sectors looking to bring new models and perspectives to net zero placemaking?

Finally, we need to recognise that we’re now at an inflection point. Just over 100 years ago, Antonio Gramsci wrote: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” Wildfires, extreme heat, rain and flooding events, and the sudden emergence of zoonotic diseases are the morbid symptoms of our time, all brought about in different ways by climate change and biodiversity loss. As we move further into the 2020s these and other symptoms will grow in frequency and magnitude. Our response to mitigate and adapt to these emerging conditions will need to be proportionately larger in scale, imagination and ambition than anything we’ve dared to dream of to date.

Karl Limbert AoU is Integrated solutions director with ENGIE UK. He has worked at a senior level in both the public and private sectors and specialises in place-based public-private partnerships and the transition to net zero