We are used to seeing strong leadership when visiting European towns and cities. Tim Challans and Steve Bee celebrated the three towns shortlisted in this year’s awards each of which has seen the local authority take the lead.

The 2022 Great Towns and Small Cities nominations; Inverness, Dun Laoghaire and Grantham; is an interesting selection as they are differently affected and influenced by the prevailing planning, investment and development cultures that support their improvement and futures. As is so often the case with the Awards process, we were not comparing like with like and reaching a balanced view was part of the challenge. We had to consider how well they are performing in the context of what is achievable, and what might all of them learn from their progress.

The 2022 Great Towns and Small Cities nominations; Inverness, Dun Laoghaire and Grantham; is an interesting selection as they are differently affected and influenced by the prevailing planning, investment and development cultures that support their improvement and futures. As is so often the case with the Awards process, we were not comparing like with like and reaching a balanced view was part of the challenge. We had to consider how well they are performing in the context of what is achievable, and what might all of them learn from their progress.

All three places share two important things. First, despite their locational advantages, they have gone through periods of decline and needed substantial and intelligent investment to strengthen and diversify their economies and ensure their futures as vibrant places in which to live, visit, work and play. Secondly, it is the local authorities that are leading the change process, working closely with other agencies. This is not unique, but in this award category we have often seen change led by community and local business action, trying to influence and persuade reluctant authorities.

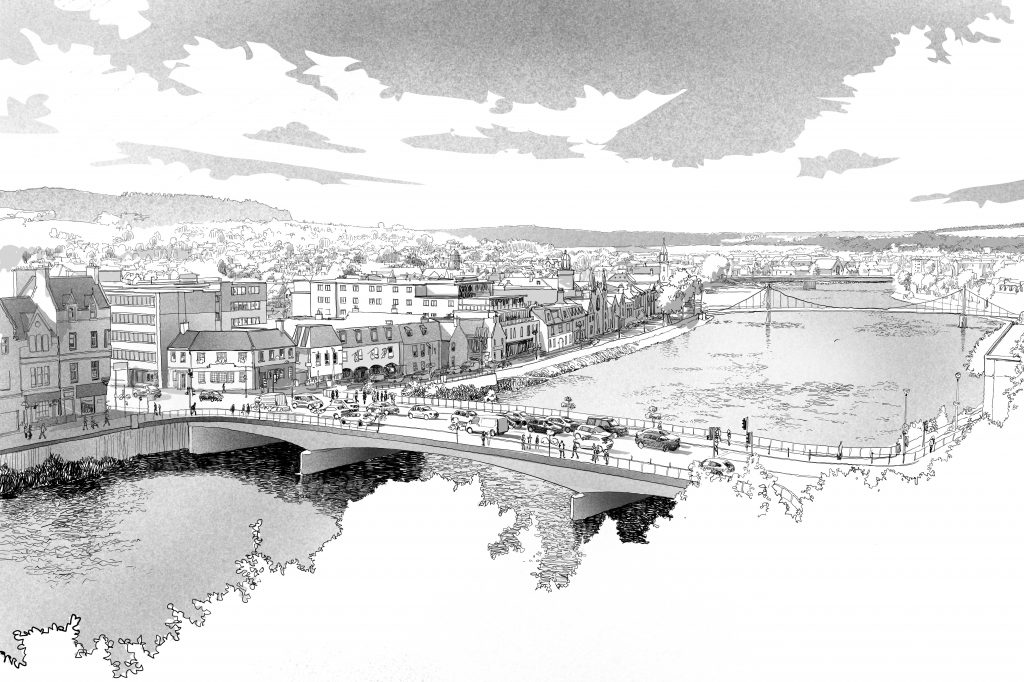

Inverness is three hours’ drive from Glasgow and Edinburgh, and the administrative centre and largest city of the Highlands and Islands region, covering an area the size of Belgium. Its economy is based on being a university city, a centre for high-tech manufacturing as well as being the main retail and tourism centre for this huge and relatively remote area. The Highland Council is the lead development organisation in the city working actively with the private sector and several other development agencies, plus the Scottish and UK governments.

These are strong and productive partnerships, and the council is committed to innovative and positive change and investment to improve Inverness commercially and socially. Its locational advantage as a visitor destination is its proximity to the Great Glen, Loch Ness, the Moray Firth, stunning landscapes and the Caledonian Canal. The redevelopment of the railway station area, the reimagining of the former law courts and the repurposing of the indoor market are examples of the city reinforcing its future as a destination. Its population is rising, and it has been voted one of the most attractive cities to live in in the United Kingdom. It has responded to reduced retail activity by introducing more city centre housing and non-retail uses as well as high-quality public realm improvements. It takes full advantage of its riverside location, as well as making the city environmentally and pedestrian friendly.

Grantham by contrast is far from remote, it is located on the busy north/south A1 and the East Coast main railway line. It developed rapidly in the 18th and 19th century as a market town and coaching stop on the Great North Road. However, despite these advantages it has suffered in the past from poor traffic management and planning decisions and a general lack of investment in its potential. It boasts the magnificent St Wulfram’s church surrounded by fine Georgian buildings, the adjacent National Trust run Belton House and has connections with Isaac Newton. Yet as a visitor destination it must compete with the more picturesque Georgian town of Stamford further south, Lincoln to the north and Nottingham to the west. The rail link makes it attractive to the commuters in the surrounding, prospering Vale of Belvoir but not as a destination to visit and enjoy.

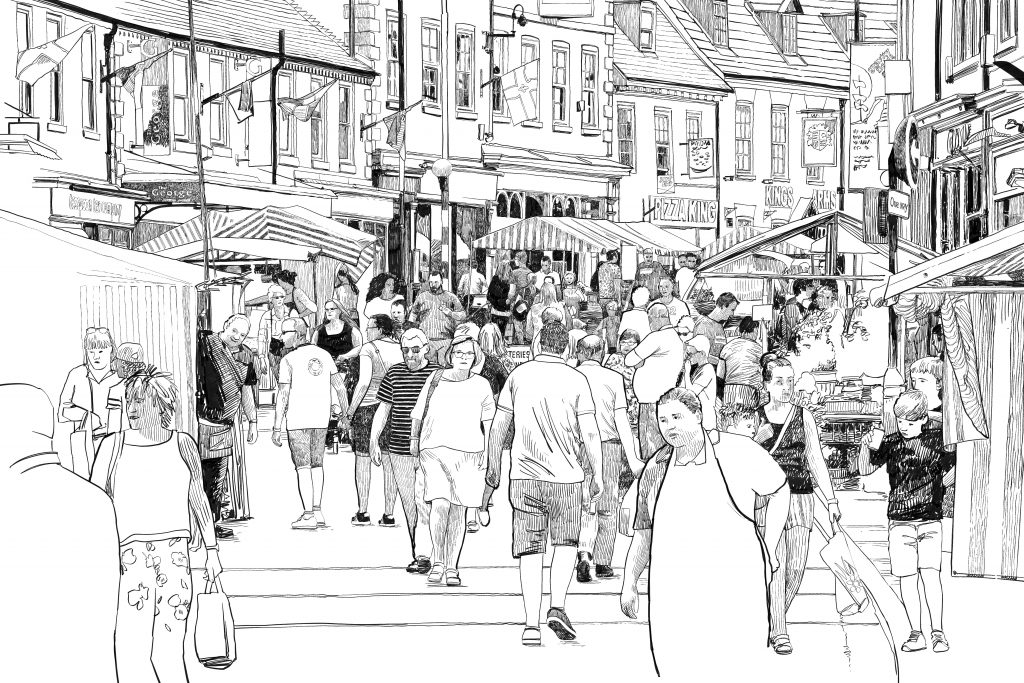

South Kesteven District Council is working with other agencies such as Network Rail, London and Continental Railways, Historic England, the National Trust, the Woodland Trust and community organisations to effect change. Politically, Grantham is the most important priority for economic and social development in the District. The declaration of a High Street Heritage Action Zone is helping to improve the high street by enabling the refurbishment and repurposing of key buildings and the creation of residential accommodation above shops. The former marketplace will be revived by removing through-traffic. There has been major private sector investment in the hospitality sector and, culturally, it has an established arts centre and a new cinema. There are plans to exploit the development potential of the area around the railway station and, critically, the pedestrian access into the town. When implemented all these measures should encourage more private investment in the town centre and its retail and hospitality offer. All of this is work in progress and the Council needs to ensure that planning decisions, such as a recent one for an outlet centre adjacent to the A1, do not undermine its own efforts.

Dun Laoghaire is a quintessentially Victorian town south of Dublin with excellent rail and road links to the city. A former safe haven for shipping that became first a port for mail boats and then the principal ferry port for Dublin, it has the feel of a seaside resort without being dominated by tourism. Despite the loss of a major employer when Stena Lines closed its service in 2014, Dun Laoghaire has built on its attraction as a day visit destination, its cultural history and coastal location. Through strong political and professional leadership, the Council took full advantage of the hiatus created by Covid restrictions to implement traffic management and other projects that have benefited the town, including temporary pedestrianisation that is now being made permanent and a coastal cycle route. Plans and developments that have been in the pipeline for several years through a series of Urban Framework documents have been implemented in recent years

In addition to making the town centre more attractive for pedestrians there have been some very significant public sector investments such as the excellent Lexicon, a public building that houses the town’s library and other cultural spaces, the repurposed public sea bathing area, the covering of the DART railway to create a landscaped promenade, the improvements to parks and public open space and the purchase of the harbour to develop water based leisure activities and to create access for cruise ship passengers and crews to the town and surrounding area. Enlightened and innovative planning decisions have ensured that new developments and improvements to the public realm take full advantage of sea views and pedestrian access to the waterside.

The principal lesson from these towns is that strong and committed local political leadership working with their professional teams, partners and local communities are still important in creating great places and civic pride. Substantial change involves risk and requires commitment. Dun Laoghaire took a real risk in building the Lexicon, resisting public criticism to create what is now a very popular public building, and in buying the former harbour to protect a vital asset. Inverness is taking a risk with a major investment in a digital visitor destination in its former law courts but has the confidence to do this.

We see this across other European towns and cities but the current weakness of local authorities in England has affected their ability to affect positive change. The civic confidence of Dun Laoghaire is palpable as is that of Inverness. Good and committed partnerships between public agencies, businesses and communities are also critical to the success and potential of these towns. Local authorities cannot achieve change without taking others with them and drawing on their resources.