The coastal Peruvian capital is renowned for both its gastronomy and its congestion. Following a recent trip to Lima Julie Plichon and Giovanni Zayas take the opportunity to reflect on the power of active travel in urbanism. The city is starting to address the latter via ‘super manzanas’ or ‘Barrios Vitales’ to boost active travel by removing through traffic from neighbourhoods.

Active travel is an urbanism silver bullet. One prescription to cure; congestion, traffic-related collisions, improve air quality, reduce chronic sedentarity lifestyles, boost people’s happiness and support local businesses. From the popularisation of the idea in Charles Montgommery’s Happy City (2013) to more technical data showing the benefits of active travel such as Transport for London’s Economic benefits analysis, or Living Street’s the Pedestrian Pound, the evidence to build a business case for active travel is overwhelming.

Active travel is an urbanism silver bullet. One prescription to cure; congestion, traffic-related collisions, improve air quality, reduce chronic sedentarity lifestyles, boost people’s happiness and support local businesses. From the popularisation of the idea in Charles Montgommery’s Happy City (2013) to more technical data showing the benefits of active travel such as Transport for London’s Economic benefits analysis, or Living Street’s the Pedestrian Pound, the evidence to build a business case for active travel is overwhelming.

The question is how to achieve a greater mode share, and whether there are universal lessons we can apply to cities, whatever their context?

The starting point is urban form although this is also the most difficult to change. It is clear that low-density, mono-use zonal US urban systems are not conducive to active travel and suffer from embedded car dependency built into their spatial development. However outside the US cities around the world, either planned or organic, achieve far better density levels and mix of use which support active travel. The question then is how these cities can plan for active travel.

Active travel infrastructure takes time to implement and embed into the city’s culture, however it can be transformative.

–

Initiatives are covered by an umbrella of terms – from the French 15 minutes neighbourhood, the British Low Traffic Neighbourhood – taking its roots in the 1970s Dutch concept of ‘filtered permeability’ and the Barcelona ‘Superblock’ or ‘super manzana’. Whilst European Cities seem to lead the way in terms of urban cycling– with the highest model shares seen in Copenhagen (where 62% of work and school trips are by cycle), Amsterdam and more recently and surprisingly, Paris, there are plenty of exciting experiments happening across the Atlantic in Latin America. From Bogota’s recent San Felipe Barrio Vital, Buenos Aires extensive pedestrianisation schemes, to Ciudad de Mexico’s cycle lane network and its expansive public bike share system.

The case of Lima is interesting. The 11 million-inhabitant Peruvian capital boasts an incredible geographical situation fronting the Pacific Ocean. In Spanish colonial style, its main street network follows a grid on a flat valley, with semi-formal settlements growing organically on its mountainous outskirts. It suffers from the air, noise pollution, community severance and marginalisation of other modes of transport that stems from the predominance of road traffic, although increasingly mitigated by a public transport and active travel offer. On the flip side, the city has an existing network of (often rather narrow) cycle lanes, designed in a Bogota fashion – taking a central position along key vehicular corridors. It has a cycling culture with its car-free Sundays on Avenida Arequipa, the historic city centre features some recently pedestrianised streets and many neighbourhoods present projects to reclaim urban space away from mono functional private traffic using tactical urbanism methods.

Just as Rome wasn’t built in a day, cycling Mecca Amsterdam didn’t exist until the 1970s. Active travel infrastructure takes time to implement and embed into the city’s culture, however it can be transformative. For Lima, the next step is to upgrade, integrate and complement a piecemeal cycle and public transport network with a superblock approach which can radically transform neighbourhoods by reallocating street space to people. Some seeds have already been sown – for instance with some tactical urbanism. The approach can be as simple as painting a pavement extension, placing a few tree pots to remove almost 80% of the traffic on a local road.

International cooperation organisations are increasingly featuring active travel within their own agendas as part of the transport decarbonisation efforts in Latin America. The World Bank, which has financed ambitious public transport projects like the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and the Metro in Lima, is offering a comprehensive technical assistance programme to government agencies, aimed at increasing capacities in planning, designing and implementing active mobility projects. International and national experts are supporting staff from the Metropolitan government in planning efforts to increase and improve pedestrian, cycling and road safety initiatives throughout Lima.

In 2020, the World Bank prepared a Bicycle Plan for Lima, featuring more than 1,100 kilometres of new bicycle lanes in the metropolitan area. World Bank staff are currently working together with the Metropolitan government on the planning, design and implementation phases of new cycle lanes from the network identified in the Plan. The Social Cost Benefit Analysis prepared for the Plan estimated that social benefits in terms of health, road safety and travel time reliability outweigh costs by a factor of 19. In addition to making progress in the implementation of the cycling network, experts are also aiding the Metropolitan government in the development of viability and technical studies for a public bike-sharing and bicycle parking system that is integrated to the Metro and BRT infrastructures.

The comprehensive capacity building initiative additionally features the development of studies that seek to update current planning and design instruments so that they can prioritise road safety and active mobility. However, beyond planning-related technical assistance, the Bank is also supporting local and metropolitan authorities in the development of communications strategies and citizen engagement plans that can contribute to a more fluid implementation of active mobility projects.

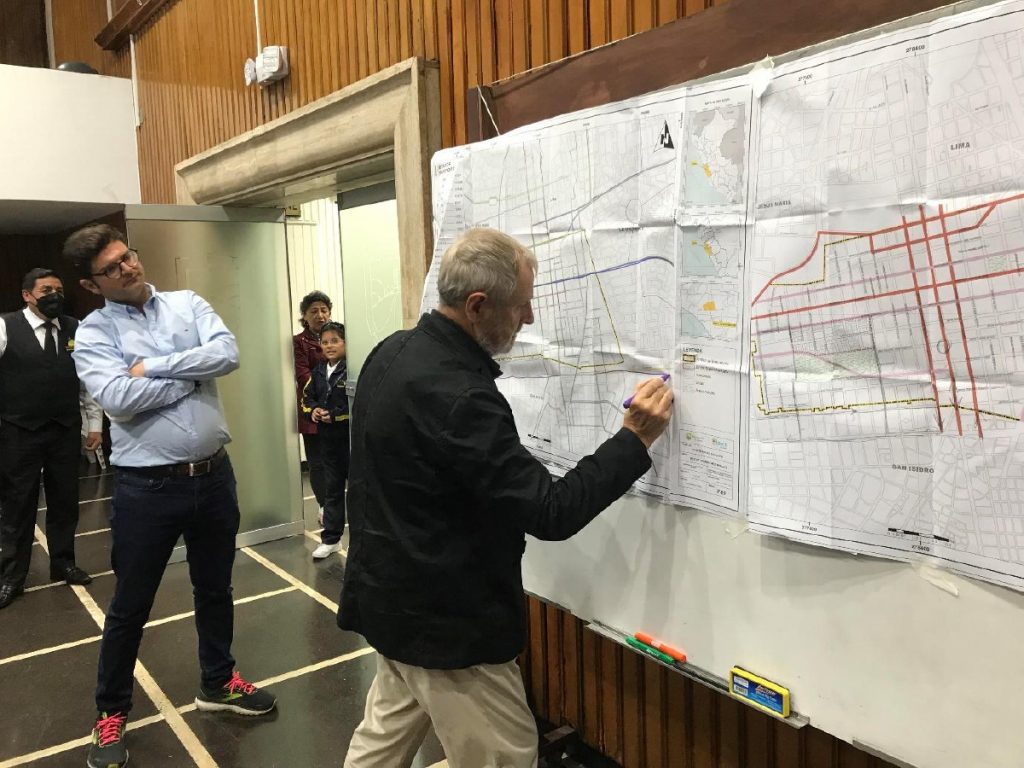

But perhaps the most innovative initiative that the Bank is supporting is the adaptation of the superblock concept in Lima districts. Staff from several local councils have had the chance to conceptualise proposals to recover public space, and improve conditions for residents, pedestrians and cyclists through a version of the Barcelona superblock that is adapted to the local context. At a recent training week for Lima’s transport planners, Salvador Rueda, the father of Barcelona’s superblocks, shared decades of wisdom in transforming neighbourhoods. Superblocks serve local connections, they transform neighbourhoods from spaces of transit into places which connect people and support the local economy by increasing customer spend through regenerating public spaces.

Another topic that is particularly key in Lima has to do with crime and insecurity – a superblock response is that more people on the street increase natural surveillance (the Jane Jacobsian ‘eyes on the streets’). The principle is always the same – neighbourhoods are transformed by removing through-traffic. The ways of achieving this are varied and each city needs to embark on its own journey – full pedestrianisation, creation of public squares, handmade or tactical urbanism, private parking removal – the many faces of superblocks, LTNs or 15 minute neighbourhoods are to be discovered.

The superblocks journey in Lima is only starting – it is no straight motorway but a windy path through political will and vision, a never ending passionate conversation about quality of life, stewardship of public spaces and citizenship.

Barcelona urbanist Salvador Rueda designing a superblock proposal in Lince, Lima. The proposal is simple – removing through traffic from neighbourhoods to reclaim and regenerate public spaces.

Main Imge: Car free Sunday in Lima. The central space is the cycle lane, the side lanes usually dedicated to traffic are pedestrianised from 5am until 12:30pm. The event offers free mechanics and goods can be purchased from cargo-cycle street stalls.