Productivity is not just the preserve of economists. New AoU Board Member Harry Knibb argues that it is a concept with a strong and often unacknowledged urban component and that towns and cities have a vital role to play in solving our productivity puzzle.

If I was an economist my solution to improving living standards in the UK would be to super charge our national productivity. I would explain that boosting productivity helps businesses produce more goods and services per unit of input. In turn, this allows higher wages, aids economic growth, increases profitability and boosts tax revenue. In short, with rising productivity we can choose to either work the same hours and earn more, or work less hours for the same wage.

If I was an economist my solution to improving living standards in the UK would be to super charge our national productivity. I would explain that boosting productivity helps businesses produce more goods and services per unit of input. In turn, this allows higher wages, aids economic growth, increases profitability and boosts tax revenue. In short, with rising productivity we can choose to either work the same hours and earn more, or work less hours for the same wage.

But I’m not an economist, I’m a planner. Planners don’t know about productivity, not in a direct sense anyway. And we’re not alone, show me an architect, engineer, quantity surveyor, sustainability and energy consultant, model maker, visualiser, or contractor (…the people actually delivering new developments now…) who understand the importance of productivity, its urban components, and how to deliver it at a project level.

For me, this is a problem. We are missing a huge opportunity to improve millions of lives across the country because productivity is seen as a topic for governments and managers, not designers and urbanists.

I believe we can use the ingredients of productivity, to understand the importance of place, and ensure we do all we can to deliver productive places. Moreover, I believe this to be a cost neutral exercise – win-win.

We need to be open to learning about the productivity of place, to help distil its ingredients and understand the benefit of delivering more productivity.

–

Productivity is a key determinant of living standards in the long term. Workers in France and the US are approximately one sixth more productive than the UK. In the US this translates to a 63% higher median income level where-as in France the higher productivity is ‘spent’ on working less rather than earning more.

The numbers are vast, if all cities were as productive as those in the Greater South East (that is, 44% more productive) the economy would be £203bn larger – equivalent to four additional city economies the size of Birmingham. Or, if our ten ‘core’ cities performed at their ‘productivity benchmark’ (an international comparison) the economy would grow by £18bn per annum.

No matter how you cut it, the UK performs poorly on the productivity rankings. Inter-nationally, we are working harder than some or earning less than others, to produce the same output. Intra-nationally, inequality is growing due to huge productivity differentials.

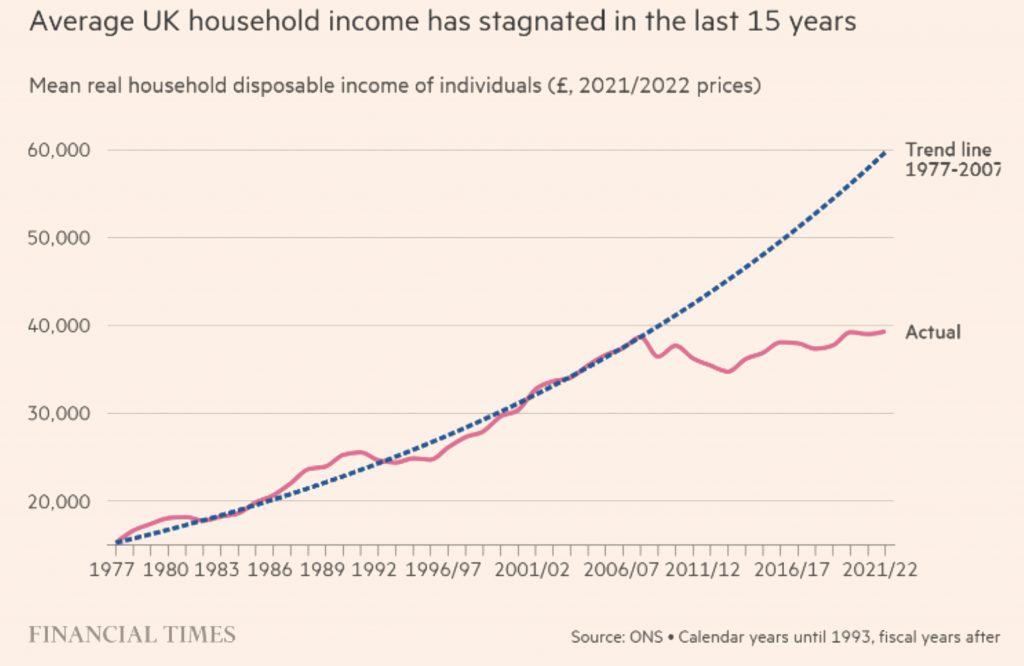

That our productivity has either stagnated or declined since 2008 lays bare the task ahead of Jeremy Hunt who pledged in his recent Spring Budget to make Britain one of the ‘most prosperous’ nations in the world. This will not be achieved without significantly improving productivity. We need a productivity rocket. Worryingly, despite this issue being recognised, considered and examined by the brightest minds, we have been unable to unlock our ‘productivity puzzle’. The implications of poor productivity growth are not solely reduced competitiveness, a faltering economy, and falling living standards, but it also impacts life expectancy which ‘has slowed down, especially for people in lower income groups’ says Jonathan Portes from Kings College. It doesn’t take much to see a vicious cycle emerge: lower living standards, impacting mental health, impacting physical health, impacting productivity, and so on…

Unfortunately, things don’t look set to change, according to the FT, the Office of Budget Responsibility has recently predicted UK household real income per person will remain below pre-pandemic levels in 2027-28 suggesting the Brits risk experiencing hardly any improvement in living standards for 20 years.

What is productivity, and what are the potential solutions?

At its simplest the UK economy, like any other, is a system which converts work into the output of goods and services. Productivity measures this rate of conversion at various levels – national, regional, city, borough, firm or individual. Labour productivity is the measure of how much output is produced per unit of labour input, for instance, per worker. Higher productivity means a business can produce more output for each worker it employs.

To improve productivity, the traditional doctrine suggests we need improvements in technology, business practices, infrastructure, and skills training. This requires investment and is very closely linked to the UK Government’s flagship Levelling-up Agenda where £4.8bn has been ring-fenced for projects throughout the UK. Whilst Levelling-up and productivity are very similar they are not synonymous. Levelling-up looks to improve living standards in the most disadvantaged communities throughout the country, productivity seeks to boost living standards throughout the whole country no matter the starting point. It lifts all boats.

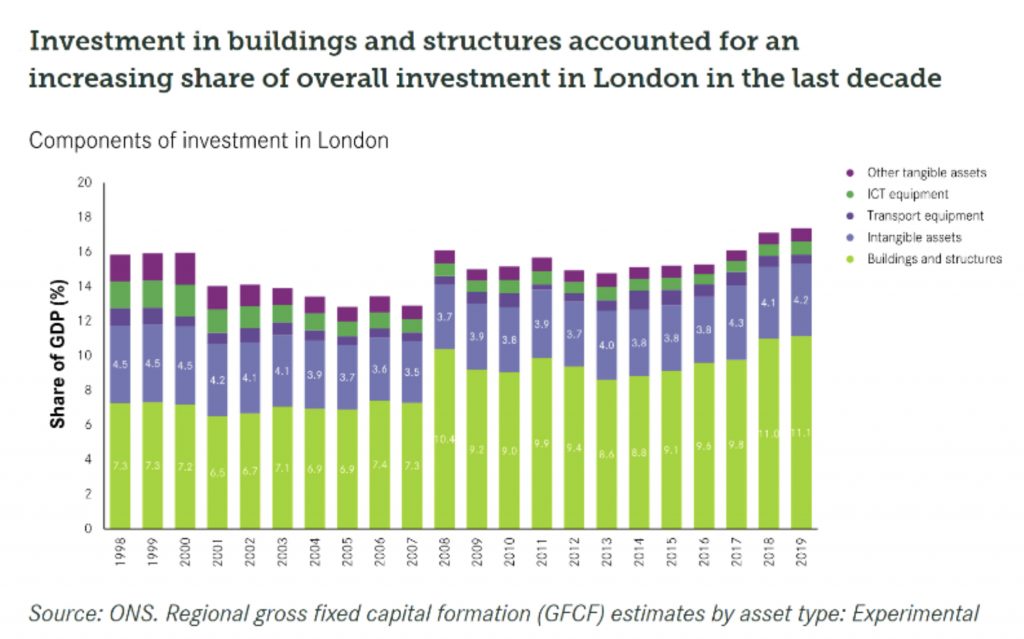

Unfortunately, within traditional productivity doctrine, little space is given to place as an ingredient of a productive country. Yet, huge investment is pumped into buildings and structures – in 2019 11.1% of London’s GDP was invested in this way up from 9.2% a decade before according to the Centre for Cities. This is a massive and growing amount of capital. Is anyone looking at these investments through a productivity lens? Yes HS2, the Northern Powerhouse and Crossrail are admirable national examples of major transport projects seeking to boost productivity through agglomeration effects from faster transit. These efforts should be applauded, but there is significant investment all over the country being delivered now, at a finer gain (building level), where designers are not considering how their scheme may, or may not, boost local productivity.

Buildings and place matter

Productivity is about people, where we live relative to our workplace, how well trained we are, how healthy we are, the knowledge we have to use technology. Within cities, the built environment plays a vital role helping to match our skills with jobs. Cities at their core are enormous labour markets which bring employers looking for skilled labour, and employees, together. This is why larger cities are usually more productive than smaller cities – agglomeration.

However, for this matching to work efficiently, housing affordability must be maintained and mobility speeds must increase as cities grow. Taking each in turn:

- Housing affordability – to grow areas of high productivity people are required. London, the UK’s most productive region has the most acute housing supply constraints. Therefore, to grow the region, houses are needed. Without this, highly skilled workers can become trapped elsewhere in low-productivity firms, making it difficult for efficient firms to expand and gain their competitive advantage. Unless housing remains affordable the labour market will distort and the city will lose productive potential.

- Transport & mobility – Alain Bertaud in his excellent book ‘Order Without Design’ argues that a city’s productivity depends on its ability to maintain mobility as it builds up. That is, as a city grows it is important to monitor mobility by comparing how average travel times and transport costs vary over time. Why? Because productivity increases with city size only if the transport network is able to connect workers with firms and providers of goods and services with consumers. This makes perfect sense, but is difficult to achieve in large cities given investment levels required. We know congestion has a dual negative effect by acting as a tax on productivity as people and goods are tied down, and it degrades the environment through increased Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Strategic planning is required and new (micro) mobility solutions could play a part as our existing transport systems are utilised more efficiently.

What can be done?

Many options exist, with the most pressing seeming to be education and planning reform. First, education. We (those working at a project level) need to be open to learning about the productivity of place, to help distil its ingredients and understand the benefit of delivering more productivity. It’s a complex subject and research is needed to robustly link the components of productivity with the components of place. Good work has started within academia, think tanks and consultancies. Long may that continue.

Second, planning reform. As a planner I see opportunity for the regulations that have served us since 1947 to be overhauled. Planning is the funnel through which all new developments must pass and has the levers to manage and improve the components of a productive city. Planning reform could improve outcomes, reduce costs, reduce timeframes, boost morale, investment, and ultimately help drive productivity. In turn living standards will increase, inequalities will drop and the UK will be on a stronger footing to move forward into an increasingly exciting yet unpredictable future.

Sounds fun.

Harry Knibb is a director at Oxford Properties and has recently become a board member of the AoU. He is a chartered town planner and developer whose work focusses heavily on large, complex and political residential led mixed-use developments.